Shoreham built, Shoreham by name fighting the French and pirates in France, Ireland and the New World.

In mediaeval times Shoreham was as productive as London as a naval shipbuilding port responsible for some of the most important naval ships of the time and even during the 17th and 18th centuries over 30 vessels of sizeable ratings were built there for the Royal Navy.

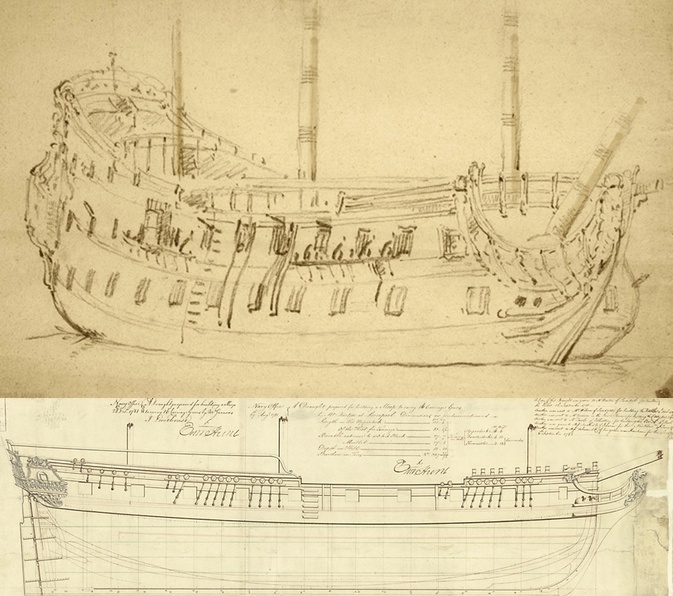

One of the largest was the fourth rate man of war HMS Dover that had three decks built at Shoreham in 1653 (1). It was armed with 48 guns and at 533 tons was so big that after it was launched it was difficult to get it out of the harbour. During its forty years naval service it captured two ships and took part in five sea battles. By comparison the smaller, unrated sloop HMS Scorpion of 1782 may only have been armed with 16 guns but it still had a sting in its tail and became one of Shoreham’s most successful ships capturing seven French privateers during its tour of duty in North America and the West Indies.

Ranked between these two was HMS Shoreham, a frigate of 362 tons classed by the Navy as a 5th rate man of war having a compliment of 135 crew (wartime home) and 115 men (wartime abroad). It was built in 1693 by Thomas Ellis at his yard south of the High Street and with 32 guns was relatively well armed for its size. During the period 1690 to 1730, 5th rate vessels were often two deckers and as it’s size, armament and crew were a little larger than the average for that rating we can realistically assume that the Shoreham was also a two-decked vessel.

Frigates were the first choice of ambitious naval commanders hoping to make a name for themselves as the vessels’ speed, maneuverability and relatively heavy armament for their size had a distinct advantage over many of the more cumbersome vessels of the time. Like the Scorpion, the Shoreham was a successful vessel in terms of capturing enemy ships. During the conflicts with France and Spain it saw service in Europe, North America, Ireland and Newfoundland taking six enemy ships (inc. a pirate ship) between 1695 and 1709.

It was initially engaged in cruising and convoy duties during part of the ‘Nine Years War’ between France and ‘The Grand Alliance’, the latter of which included Great Britain, Holland and Spain. It was this conflict that drew the Shoreham into a disastrous start and almost prematurely ended its career.

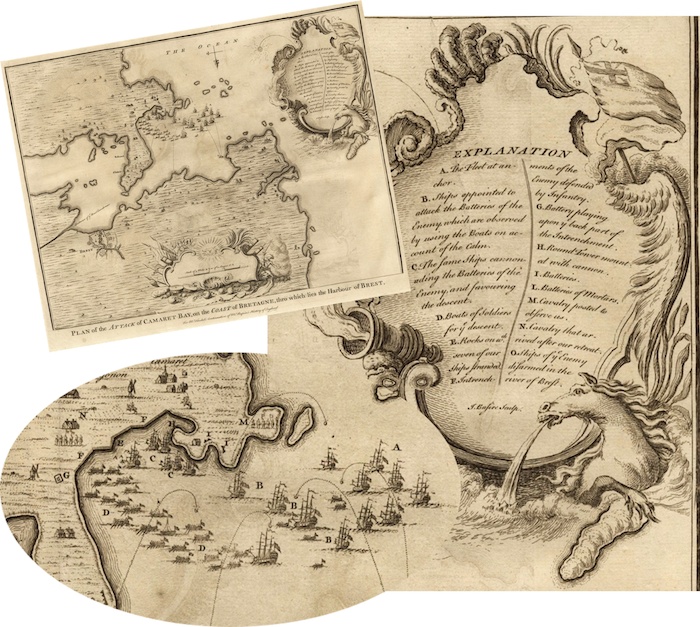

On the 18th June 1694 an attempt was made by the English and Dutch within the Alliance to seize the port of Brest and destroy the French fleet moored there in Camaret Bay. A fleet was assembled in Portsmouth consisting of 36 warships, 12 fireships and 40 transport ships, carrying an invasion army of 10,000 soldiers under the command of general Thomas Tollemache. Poor planning and lack of local intelligence though resulted in huge casualties on the Alliance side. The Shoreham was one of seven ships that were moored above rocks on which they became trapped as the tide receded during the attack. The helpless ships were overlooked by cliffs away from the fortified areas and subsequently it was largely small arms and light cannon fire to which they were subjected. This was little consolation though during those long hours between tides. In such a vulnerable position, being fired on from above and unable to bring their own guns to bear they suffered terribly. It seems though that the hull was undamaged by the rocks and, commanded by John Constable and with the returning tide, the Shoreham eventually managed to refloat and escaped.

On the 25th July the following year the Shoreham scored her first success with the capture of a privateer corvette named ‘Farouche’ or ‘La Feroa.’ Records vary as to the name. Sadly the log for this period is in too delicate a condition to scan so for the moment the details of the action must await a personal visit to the National Maritime Museum.

Philip Dawes was appointed as the second commander of the Shoreham in 1697. Dawes had sailed under the command of Admiral John Benbow (as John Constable was later to do) during the attack on St.Malo in 1694. The Admiral had pioneered the use of ships as missiles during the attack, known as Infernals they were loaded with explosives and sailed into the port then detonated. Dawes had been master of one of these vessels, the Machine, and must have conducted himself satisfactorily (and jumped off in time) for he was soon after promoted to the command of the Shoreham. Nothing of significance though seems to have occurred during his time on the ship and he was succeeded in 1699 by William Passenger who had also previously commanded a fire ship, the Vesuvius, that by coincidence had been built in Nicholas Barrett’s shipyard at Shoreham in 1693, the same year as HMS Shoreham.

Passenger was Shoreham’s commander for five years that included duty in North America and it was here in April of 1700 that the Shoreham was involved in an epic ten-hour battle with a pirate ship.

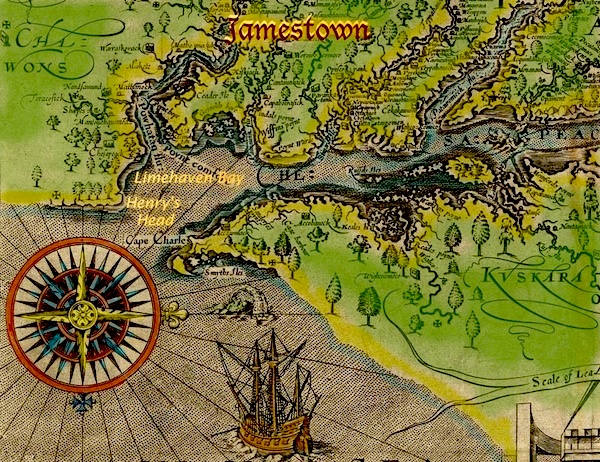

On the 29th April the ship is logged at Lymehaven Bay, Virginia at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay (now known as Lynnhaven Bay next to Henry’s Head) taking on water supplies. The Shoreham was at this time very short handed compelling Captain Passenger to take on inexperienced and underage sailors. News was received that a pirate vessel that had been causing a number of ship losses had taken two Virginian merchantmen so Passenger set sail and at ten-o-clock that night came to anchor three leagues short of the pirate. Francis Nicholson, the Governor of Virginia, aware of the forthcoming confrontation came on board the Shoreham together with Captain Aldred of the ship the Essex Prize (an inadequately armed vessel that had earlier been mercilessly outgunned by the same pirate) and Peter Hayman, a Customs Agent from nearby Hampton who had volunteered to join the action.

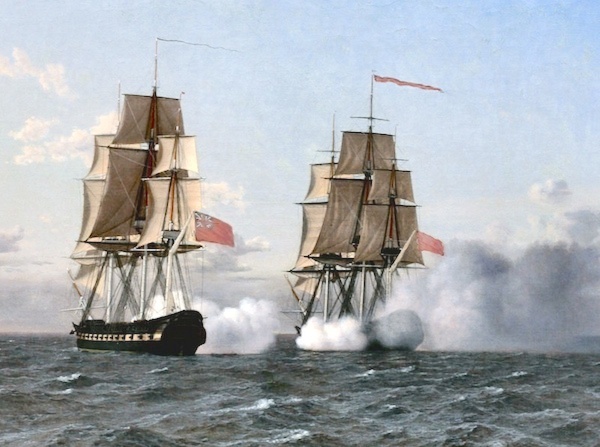

At three in the morning they weighed anchor and approached the pirate who loosed his topsails with the intention of getting to windward of the Shoreham in order to board her – as Passenger later wrote in his log the pirate thought the Shoreham would be a pushover ‘this is but a small fellow we shall have him so gently.’ The pirate turned out to be the La Paix (Peace) of a size ‘above 250 tons, 20 guns (one record states with 8 more in the hold) of which 9 were mounted and crew of 150 fighting men.’ It was of a similar size to the Shoreham but the English ship was unable to use all its guns through lack of sufficient gunners. The Shoreham fired one shot and in response ‘the pyrate immediately hoisted a red jack ensign and a broad pennant and returned my thanks’ – i.e., he returned the fire. Pirates generally used two flags or jacks as they were called (not to be confused with union jacks) – a black one denoting that quarter would be given if their adversary surrendered and a red one indicating no quarter – the pirate was threatening to slaughter the Shoreham’s crew!

Back on land word had got round and a large crowd had assembled to watch the fight. At 5 am the battle commenced with both ships manoeuvering and counter manoeuvering in an effort to avoid or enable a boarding party attack and firing cannon whenever it was possible to bring them to bear. Often they were close enough to be within pistol shot of each other and during these moments even Governor Nicholson took part firing his own pistols at the pirate crew from the Shoreham’s quarterdeck. One murderous volley from the La Paix killed the luckless Peter Hayman as he stood next to Nicholson.

Passenger continued to demonstrate a high degree of seamanship in maintaining his ship’s positional advantage to avoid being boarded by an enemy of greater numbers and inspiring courage in his crew of boys and short-handed gunners in the face of murderous fire from the pirate. The Shoreham had lost its mainmast but was wreaking its own retribution though and at one point there were so many bodies on the ‘La Paix’s’ deck that the dead and wounded seamen had to be thrown overboard.

Over an incredible ten hours of fighting the pirate’s mast yards, sails and rigging were ‘all shot to tatters, several guns were unmoored and their hull almost beat to pieces.’ At this point cannon fire from the English ship smashed the pirate’s rudder and the helpless ship ran aground. The Shoreham drew up and anchored ‘within pistol shot’ but, to avoid the pirate’s guns, not alongside the pirate vessel and terms of surrender were negotiated from out of the cabin window at the stern.

The pirate captain was Louis Guitter, a Frenchman originally from St. Malo and he tried one last ruse to avoid surrendering by priming 30 barrels of gunpowder with which to destroy the pirate ship and the 50 captives he had on board besides seriously damaging the Shoreham itself. Governor Nicholson promised quarter and a trial by jury. During the fight the pirate had suffered 26 crew killed and about 50 wounded. 124 of the pirate crew surrendered of which three were tried at Hampton and hanged on nearby beaches as a warning to others. The remainder including Guitter were sent to London where they were tried and all hanged.

With the La Paix were two ships the pirates had captured previously but Passenger doesn’t name them. He does though list some of the ones, all Virginian merchantmen, that had been taken by the La Paix – the Indian King 500 tons, Mr Whittaker master; Nicholson 500 tons and 14 guns, Mr. Lucking master; George a sloop, Joseph Forester master; Baltimore, a pink and Pennsylvania, Samuel Harrison master. The pirates had looted this last vessel then set fire to it.

Of Guitter, the French captain, Passenger writes ‘He has not been captain of them above 8 months but several gangs of notorious rogues the major part French with some English and Dutch have joined together which have committed abundance of outrages and villainy in a hostile and pyratical manner murthering of men in cold blood sinking burning plundering and destroying of ships.’ We know a little of his appearance and nature from the captain of one of the captured ships who described him as a man of middle stature, square-shouldered, large jointed, lean, much disfigured with the smallpox, broad speech, thick-lipped, a cast in his left eye, but courteous.

He had taken at least nine ships including the ‘La Paix’ a Dutch ship that he used for himself, as well as many prisoners from them using torture if they refused to join as pirates. Guitter had kept alive on board some 40 to 50 of his prisoners perhaps for use as hostages. These were masters, merchants and seamen that Passenger returned to their own ships.

The Shoreham had lost four men killed (including the luckless Peter Hayman) and six wounded – a seemingly light casualty rate bearing in mind the intensive fire indicated by the descriptions of the battle. Damage to the vessel was reported as ‘…sails, rigging were all shot to pieces, the mainmast shot through with double head and round shot so unserviceable there is a new mainmast a making and I am fitting my rigging with all possible dispatch…..’

After returning to England in 1702 the Shoreham was sent to Ireland to protect and convoy local trade. It was during the War of Spanish Succession when Great Britain and Holland formed an alliance against the French. William Passenger remained with the Shoreham until 1705 when he was promoted to take charge of more important ships including the first rate Royal Anne of 1,720 tons armed with 100 guns. His replacement was George Saunders during patrols between Whitehaven, Milford and Bristol on the English/Welsh coast and on the Irish coast from Belfast to Kinsale.

Saunders made two successful captures, the first was on the 5th June of 1706. HMS Shoreham shared the Irish convoy duties with the Hampshire and Speedwell. The log book entries three days before are interesting enough to bear special mention. At Kinsale harbour the Shoreham fired 17 guns in celebration of the Duke of Marlborough’s overwhelming victory defeating the French at the Battle of Blenheim. The next day ‘little wind and calm’ was entered followed by ‘warped out of the harbour in company with the Speedwell.’ When opposing winds or a dead calm prevented progress a kedge anchor was taken forward in a rowing boat then dropped and hauled by the ship’s crew thereby pulling the boat forward. The process was repeated until the ship made open water or the wind improved. With both ships using this method to proceed it must have been a fascinating sight to watch and would often have been used at Shoreham.

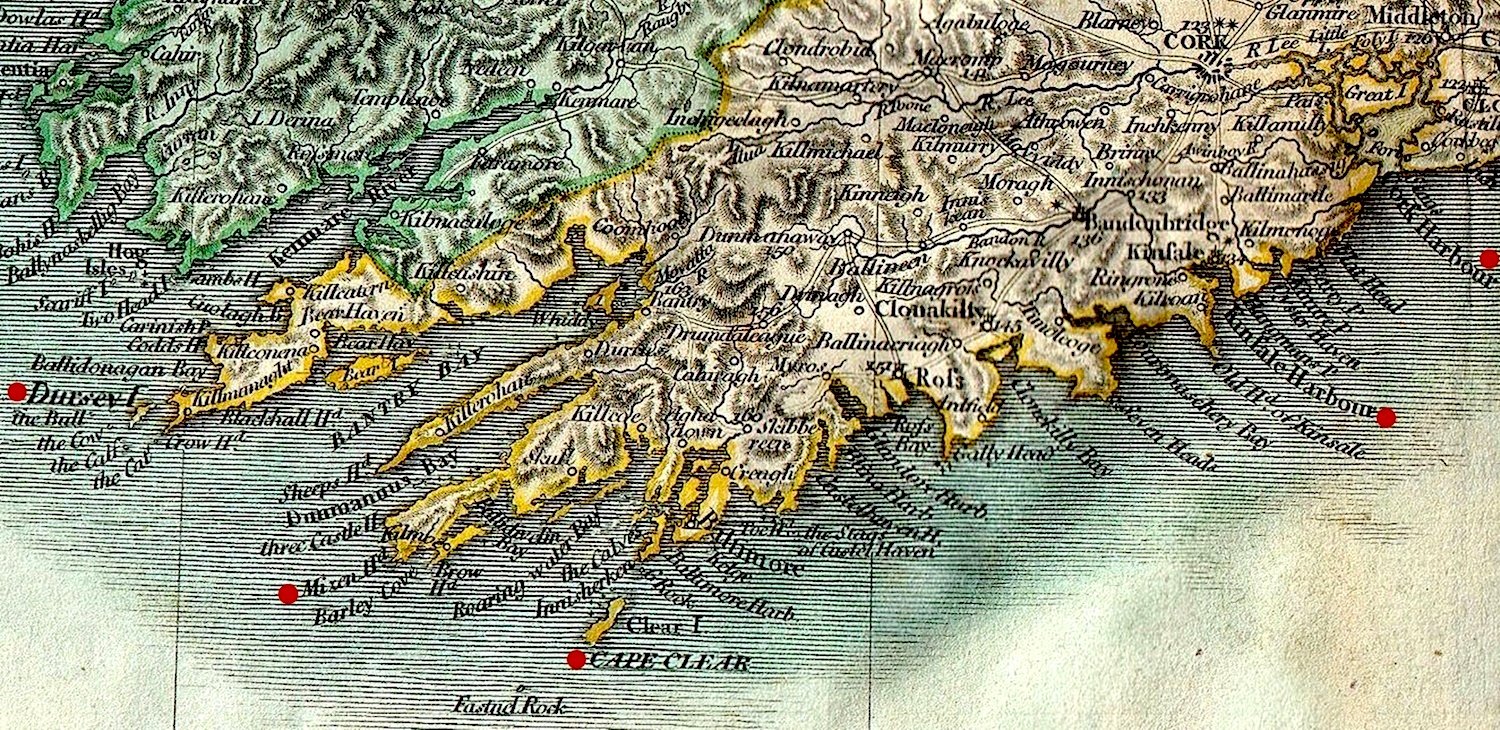

By the 4th June the winds had picked up and at 6pm at Mizen Head, Ireland’s most south-westerly point between Dursey Island to the north and Cape Clear island to the south, a sail in the distance was spotted and the ship gave chase. Naval action in those days often took many hours to engage and the chase continued through the night to Dursey island and by 5 in the afternoon the next day after 23 hours they finally reached the pursued vessel. This ‘proved to be a French privateer of 8 guns belonging to Sharbrock’ (2) – After what the log entry describes as ‘a small dispute’ the Shoreham shot away the ship’s main topmast and it surrendered just south east of Dursey Island.

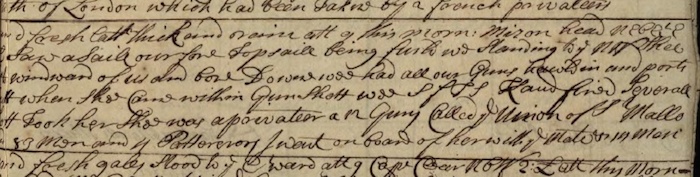

Three years later on the 19th May 1709, still under the command of Saunders and again at Mizen Head, a sail was seen in the distance ‘our fore topsail was furled we standing to the north west and windward of us and (we) bore down we had all our guns hauled in and ports shut when she came within gunshot and fired several shot took her. She was a privateer of 12 guns called the ’Union’ (3) of St. Malo and 83 men and 4 passengers. I went on board of her with the mate and 19 men. Sent all the prisoners on shore at Kinsale Bay.’

For the next ten years patrol and convoying duties continued in the Irish Sea following which the ship was commissioned for New York. The Shoreham had three further commanders during this time but no further events of any consequence are recorded. Extensive repairs were carried out at Sheerness in 1715 costing a significant £2,000 but despite this the Lords of the Admiralty decided four years later that the ship was to be broken up and rebuilt.

That was the end of the Shoreham as it had been. Nevertheless there would have been a significant amount of timber used from the earlier vessel added to which the rebuilt ship was given the same name so perhaps she was still the old Shoreham at heart. She served between New York and the Caribbean protecting ships from Spanish privateers and even captured one that was carrying a reported 800,000 pieces of eight although other reports suggest this was nearer 30,000 pieces but even then worth £70,000 at the time.

The second HMS Shoreham was eventually sold off at Deptford in 1744.

- The Dover was classed as having two decks but in naval classification of the time these were two ‘gun’ decks (in addition to the top, outside deck) primarily used for the mounting of cannon.

- Perhaps Cherbourg? – the ship was probably the Francis mentioned by Henry Cheal in his book.

- Henry Cheal records this vessel as the L’Esperance.

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

February 2015

Known commanders of HMS Shoreham:-

1694/1695 John Constable

1697 Philip Dawes

1699/1704 William Passenger

1705/1709 George Michael Saunders

1710/1711 John Furzer

1711 Charles Hardy

1713 Edward Falkingham

after rebuild:-

1715/1718 Thomas Howard

1721/1724 Covill Mayne

1727/1730 Robert Long

1731/1732 Thomas Griffin

1732/1737 John Towry

1738/1741 Edward Boscawen

1741/1742 Thomas Broderick

Explanation of the Camaret Bay illustration:-

English: Plan of the Attack of Camaret Bay, on the Coast of Bretagne, thro which lies the Harbour of Brest.

For Mr. Tindal’s continuation of Mr. Rapin’s History of England

Explanation:

- A: The fleet at anchor.

- B: Ships appointed to attack the Batteries of the Enemy which are observed by using the Boats of the Cahn.

- C: The same ships cannonading the Batteries of the Enemy and favouring the descent.

- D: Boats of soldiers for the descent.

- E: Rocks on which seven of our ships stranded.

- F: Intrenchments of the Enemy defended by Infantry.

- G: Battery playing upon the back part of the Intrenchment.

- H: Round Tower mounted with cannon.

- I: Batteries.

- L: Batteries of Mortars.

- M: Cavalry posted to observe us.

- N: Cavalry that arrived after our retreat

- O: Ships of the Enemy disarmed in the river of Brest

Sources:-

Lieutenants Log extracts from ADM/L/S267, 268 and 270; Images of the Dover, Scorpion, 1690 Frigate and the 1709 log book all from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

‘Ships Built or Registered in Shoreham’ by Roger Bateman

British Library Newspaper Archives

http://bravebenbow.com – the story of Admiral John Benbow and the Benbow Mutiny

Three Decks – Warships in the Age of Sail at the website at http://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=6684

‘The Story of Shoreham’ by Henry Cheal

‘The Ships and Mariners of Shoreham’ by Henry Cheal

‘Ships of the Old Navy’ website by Michael Phillips

Calendar of State PapersColonial, America and West Indies, Volume 18, 1700. 523. ii at British History on Line

Guittar Family History at Genforum.genealogy.com

‘Governor Goes Head to Head with Pirates’ article by Mark St.John Erikson Daily Press 2015

18th century map of south-west Ireland from Geographicus

Shoreham shipyards from Captain John Butler’s 18th century drawing at Marlipins Museum, coloured version from Shorehambysea.com