John Hindes, a Durham born man with a seagoing background, came to know Shoreham as a crewman during frequent visits in the coal-carrying sailing ships from the north east that traded with Sussex ports in the years following the Napoleonic Wars.

Not just a merchant sailor Hindes was also a war hero. He spent the first ten of his adult years in the service of his country with the Royal Marines during which he ‘fought and bled for his country in the Battle of Trafalgar, and with Sir Samuel Hood, off Rochfort; likewise assisting at the taking of the Isle De France (Mauritius), Java and Beunos Ayres’ during which time upwards of one hundred and fifty two ships and vessels were taken. (1)

He was a Royal Marine private from RM Headquarters at Portsmouth, and is shown in an 1805 ship’s pay book for HMS Polyphemus (2). That ship saw action at the Battle of Trafalgar, towed the much damaged HMS Victory carrying Admiral Nelson’s body back to Gibraltar after the battle and was subsequently involved in four of the battles that were attributed to Hindes. The Naval General Service Medal Roll collection shows the Polythemus Royal Marine John Hinds as being awarded the Naval General Service Medal with the Trafalgar clasp in 1848 but the strongest evidence of his service though has to be his pension. John was wounded at least once – wounds received in those times were the only reason for lower ranks being awarded a (very) small pension along with the title ‘Greenwich Out-Pensioner.’ It was the subsequent withdrawal of this pension under controversial circumstances that were widely reported in newspapers of the time.

Described variously as a ship’s carpenter and shipwright he first appears in local records through his marriage in 1821 to Sarah Martin, a widow of Shoreham. The couple set up home initially in the newly developing New Road area later moving to one of the small cottages in Middle Street. Over the years nine children were born to them (3) otherwise life appears to have been uneventful until he became involved in certain events that were to change his life significantly.

Trouble with the Authorities and the Steyning Union

In 1834 there was an important change to the town’s administration, the circumstances of which are not generally known. Townsfolk were being informed of the intention to join the parish to the Steyning Union. Shoreham had for some time adequately supported the relatively few poor of the town, rarely more than eighteen at any one time, at its own poor house on the corner of St.Mary’s Road with Pond Road. Rather than force the impoverished into the workhouse the practice was to provide financial aid to purchase, say, a horse and cart or boat giving them the means earn their own living. This had all been achieved without a strain on townsfolk’s contributions through the Parish Poor Rates (the early form of council tax) but if responsibility for the Steyning Union was now to be included the fear was that, even with the income of the other towns within the Union, the responsibility for the increased number of dependents would cause the rates to escalate.

A meeting was called. The majority of the town were against the union but those rated under £50 had only one vote whereas those rated at £150 had six so that the more wealthy ratepayers who were largely in favour had a disproportionate advantage! On top of all this one local employer who wanted the Union had many employees and through them further influenced the outcome of the vote. Three Guardians were appointed and the proposals were set up to be passed when John Hindes who was in attendance moved for an adjournment so that townsfolk could have more time to appreciate and understand what effects the union was likely to have. The chairman of the proceedings, William Tate, undemocratically refused the request and the union was pushed through resulting in the building of the new workhouse in Ham Road with Shoreham taking inmates from the surrounding parishes.

On another matter though John would have ruffled ecclesiastical feathers somewhat. He had been something of a crusader for the poorer folk in 1834 when he took a stand against the local clergy who wanted to erect a wall and level some graves of the less well to do in St. Mary’s churchyard who’s relatives hadn’t been able to afford gravestones. The outcome was successful for John but as far as the church authorities were concerned his card was marked.

In early 1837 John took occupancy of a beerhouse further down Middle Street on the south side of the house that later became the Royal Sovereign. He named it ‘The Durham Arms’ in recognition of his origins. John was born in Durham, family ties with that area were maintained over the years and one of his sons, John Charles Hindes (b. 1826) later moved to South Shields, Durham where he became a Dock Inspector on the Tyne there.

John’s beerhouse was the scene of an earlier involvement with the law where George Walkley was arrested in possession of stolen goods, a silver spoon. Jane Miles, a witness and lodger, is described as ‘a girl of bad character’ (4) so all in all the premises were unlikely to have had a particularly good reputation. George Butler, one of the Shoreham parish constables or headboroughs as they were also known, was the arresting officer and he figures prominently in the subsequent events.

Whilst carrying out the arrest and investigations at the Durham Arms, Butler was already aware of the situation there which became evident as the trial moved on to discuss the beer shop itself. An extract from the Walkley trial on Thursday 15th March 1838 reveals Hindes (here referred to as Hindus) to be unawed by the proceeds, quotes his naval record as evidence of his standing and even gives as good as he gets in crossing swords with the magistrates:-

Frances Standing had stated that she and Jane Miles were two of five girl lodgers at the time.

Mr. Seymour (Magistrate) to Hindus – Do you mean to say that you don’t let your house to these girls knowing them to be prostitutes?

Hindus – I deny that my house is a receptacle for prostitutes.

Mr. Seymour then called Jane Miles and asked her if Hindus was not aware that his lodgers were girls of the town?

Miles – Of course he is.

Seymour – If you don’t indict this house, Mr. Butler, you will not be doing your duty.

Hindus (with warmth) – My character stands high in the Navy and as high as any man’s in Shoreham.

Seymour – Can you deny what these women say?

Hindus – Am I to debar seafaring men from coming to my house more than others?

Seymour – A burglar would talk like that. He would say ‘Will you hang me for a burglary when there are so many other burglars?’

Hindus – Do you mean to say then that I am a thief? (laughter)

Seymour – the tenor of your licence is that you shall not knowingly permit persons of bad character to assemble at your house. I find the Shoreham people rather thin-skinned when accused of keeping disorderly houses.

Hindus – No more thin-skinned than the Brighton people.

Jane Miles was then re-examined and stated that Hindus knew that she had the spoon (stolen by Walkley) and said that if she said anything about it he would turn her out of the house.

Seymour Now Hindus, what do you say to that?

Hindes – I deny it.

Another witness then corroborated the statement of Miles with regard to the threat about the spoon………..

Seymour – Have you any doubt Mr Butler that this man keeps a disorderly house?

Butler – If I said I had I should tell a falsehood.

Mr Seymour again told Mr Butler that he would neglect his duty if he did not indict that house.

In his further defence John stated that being a seafaring man he allowed fiddling and dancing at the house with the sailors and their girls as it was generally allowed at most seaports including this house before he took it. (5)

George Butler is clearly being pressed by the magistrates to pursue the indictment of John Hindes who is denying the accusation. It may seem unlikely that small cottages such as those in Middle Street could accommodate the five girls in addition to John’s large family of nine children until you realise that the two cottages standing immediately south of The Royal Sovereign were originally one building and still sport the original, single doorway that now branches off either side to two separate front doors. By way of further example the premises were a few years later used as a lodging house when no less than 25 persons were recorded as residing there overnight! It was converted into two properties in the early 1900’s and still bears the 5 and 5a numbering that resulted.

As a trading port for many centuries Shoreham had a regular coming and going of itinerant sailors that inevitably included a following of ‘ladies of the town’ as they were known in the 19th century. Not necessarily permanent Shoreham residents as the name may imply but, like the sailors themselves, moving from town to town in pursuit of ‘employment.’

Shoreham looks to have had something of a problem as, in addition to the alleged ‘bawdy house’ in Middle Street there were also investigations being carried out of ‘an house of ill fame’ in the town run by a Mr & Mrs Morley who had permitted prostitutes to take lodgings at their house in Church Street. Fears were voiced as to the ‘youth of both sexes being exposed to the deadly allurements of these sinks of iniquity……..wives and daughters cannot walk the streets without being disgusted by the language and behaviour of prostituted women.’ (6) There was even some concern for the girls themselves when The Rev. William Singleton of Shoreham reported the deplorable condition of the prostitutes and one in particular he had spoken to who confessed she was weary of life. A situation that, it was expected, was likely to worsen with all the young labouring men that would accompany the forthcoming building of the Brighton to Shoreham railway.

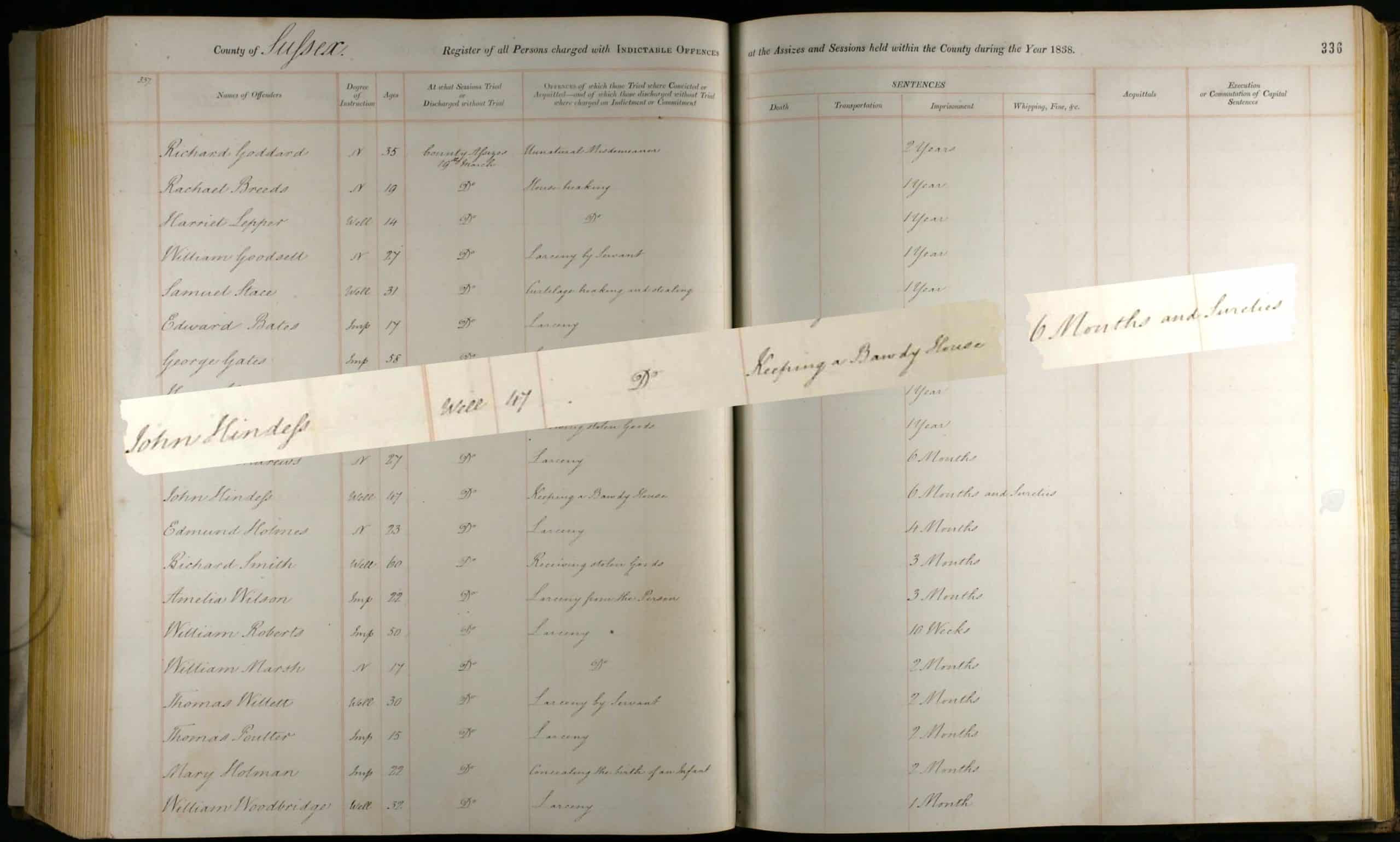

Needless to say Butler complied with the magistrate’s wishes to pursue the prosecution which concluded with Hindes’ conviction and sentencing at the Spring Assizes on 19th March 1838. Although he initially denied accusations subsequent reports reveal that he later changed his plea to guilty. (7) At this point in the story the events surrounding the prosecution as well as another, similar incident of the time brings into question the legitimacy of the verdict and it is pertinent to look at George Butler in more detail.

Who was George Butler?

George was the son of John Butler of Church Street, captain of the customs cutter ‘Hound’ and father of Maria, the authoress of the Butler family history whose life was so tragically cut short by tuberculosis or consumption as they called it then (8)

George and his brother Robert were builders. They had built the largest surviving Georgian house in Shoreham now known as Westover that stands at the top of Church Street facing Pond Road, and were involved with others in developing parts of the east end of the town in the King’s Arms Fields, including New Road and Surrey Street.

They also built their own houses there. In quality and appearance these were a cut above most of the other houses in the area, an attractive pair of semi detached buildings with impressive classical verandahs set back on the north side of New Road that nowadays still stand on the north-eastern corner with Surrey Street.

Then as now, criminal occurrences were eagerly pounced upon and reported by the local newspapers and Shoreham received mention frequently indicating perhaps that it had a particular problem, not just with houses of ill repute but all types of crime generally. In fact it was felt that there were enough cases to warrant some county court sessions to be held in Shoreham and they were! Often appearing amongst the names of lawmen investigating and arresting the culprits was George and from the description of his exploits he can be seen to have been particularly diligent in his investigations.

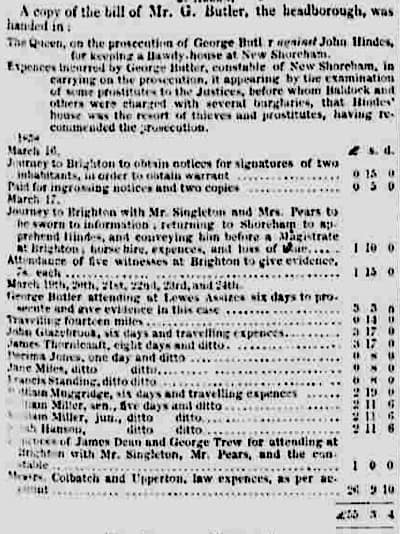

He often worked with his brother, also a constable, but their duties were not well paid consisting mostly of expenses claimed out of the Parish Poor Rates ‘according to the duties they performed’ and inevitably required the job holder to be earning another income. In prosecuting Hindes George was supported by Shoreham vicar the Rev. Singleton. The constable’s association with the church is also reflected by the fact that George also later provided lodging at his house to no less than clergyman Nathaniel Woodard and his family, founder of Lancing College and other colleges within the Woodard Corporation. Both George and the Rev Singleton though were to become severely criticised when their claims for the expenses incurred in the prosecution of Hindes came to light as well as a later accusation of ‘fixing’ in a similar case.

The amount claimed and the items being charged for were the subject of a Vestry Meeting in Shoreham in the girl’s school-room of the National School (on the north-east corner of New Road with East Street) to consider the extravagant and extraordinary expenditure incurred in the prosecution of a keeper of a house of ill fame named Hindes. The total amounted to £55.3s.4d, a considerable sum in those days. Perhaps the magistrates’ urging George to prosecute Hindes encouraged him (George) to claim the maximum amount possible even for some trifling matters. One of the criticisms was that George had charged for time spent at Lewes (assizes court) on a different case altogether and that other charges were made as heavy as possible.

The Rev. Singleton, campaigning to clear the town of prostitution and present at the time of John’s arrest, was also criticised for claiming sums that it was felt being a part of his job as a clergyman should have been carried out for nothing. Butler also felt he was being unfairly criticised but something of his attitude can be seen when on being asked by an overseer of the Vestry Committee (the Shoreham body responsible for charging and receiving rates paid by parishioners and paying out such payments as those incurred in the Hindes prosecution) for more time to pay threatened ‘I’ll give you no time but will go over to Brighton if it is not immediately paid and immerse you in double costs.’ In the event it was ruled that George should receive payment but it left a bad feeling in town for a long time after.

George’s methods and something of his personality were to come under fire again some time later when a stinging local newspaper report contained slanderous comments of him. (9) ‘Last Monday Butler, our sapient headborough was at his dirty work again. It seems the Brighton bench is tired and surfeited with his officiousness.’ The report though went even further and implied that George used three local prostitutes and some sailors to create a breach of the peace outside the Crown & Anchor pub in the High Street for which George ‘got his inducement, half the fine and his share of the costs and the girls are still on the town looking out, no doubt for more dirty work.’

The newspaper, the Brighton Patriot, was well known to have Chartist leanings and often openly supported the working man in cases of discrimination. In doing so though it perhaps published contentious reports that sometimes exaggerated the facts – did it do so in this instance? By now John was into the third month of his sentence and whether or not the accusation concerning Butler was true or false the matter was not followed up and nothing further is known. Nevertheless, that newspaper’s support of Hindes in later developments was to prove particularly welcome to John and his cause.

Imprisonment, Physical and Mental Torture

Returning to Hindes’ sentencing which, with sureties, was set at just six months – for those times a seemingly short period when punishment was usually so severe. More pertinent though are the conditions variously described as ‘hard labour’ and ‘six months at the treadmill’ (10) which was to be carried out at the notorious Petworth House of Correction, the main prison for offenders from West Sussex.

John was no stranger to Petworth as he had earlier been tried and sentenced at the 1832 Quarter Sessions for some lesser or petty offence. This punishment did not involve the treadmill though and, in any case as it turned out, he contracted smallpox and spent the whole of his sentence in the prison infirmary. (11)

Prisoners were subjected to a strict regime that kept them in sole confinement with no communication with other prisoners at all and could only speak to answer questions from the prison officers. A debilitating noiseless atmosphere that was rigidly enforced even to the extent of officers wearing soft shoes. The ‘hard labour’ bit meant he had to serve his sentence on one of the infamous treadmills there. In fact one of the newspaper reports of his sentence refers to it as ‘a particularly cruel, soul destroying and dangerous ordeal with no purpose other than to punish.’

It wasn’t just a gradual treading on the wheel, a minimum speed of 48 steps per minute had to be taken stepping through 11,340 feet within a time limit of ten hours in the summer or seven hours in the winter. All this on a contraption that did not even provide a handhold so if tired prisoners stumbled they risked falling on the wheel and being mutilated underneath it, many were and some lost their lives, children included.

Petworth also had another hard-labour machine for men and women called the ‘crank’. 30 prisoners at a time had to each turn a handle against a resisting pressure – 13,200 times in a 10-hour day. (13)

The family was now without any income now that John was serving his sentence and, apart from minimal financial help from the Vestry Committee, his wife Sarah and the children must have found life quite desperate. There is some indication of this at the time when one of his daughters, also Sarah, aged 18, was convicted of stealing a silver spoon and sentenced to six months imprisonment the first and last fortnights of the third and sixth months in solitary confinement, the remainder of the term to hard labour. (14)

If as seems likely, the sentence was carried out at Petworth then father and daughter had the dubious distinction of serving their sentences in the same place at the same time. If she managed to avoid the treadmill then she would still have had to endure the crank and of course the agonising regime of silence and isolation.

John survived his time at Petworth but on his release learned that he had his licence to sell beer taken away owing to his offence. He moved with his family to Barrack Gardens in Ravens Road and having lost his livelihood had to look elsewhere for employment. Times were difficult but he was to find life even harder when the Admiralty suddenly withdrew his small pension!

Chartist Meeting and The Battle for the Pension

Some thought that part of the reason for the loss of his pension was John’s conviction for running a brothel but for John the real reason he believed was his attendance at a Chartist meeting in Shoreham.

The Chartist Movement arose after the 1832 Reform Act failed to extend the vote beyond property owners. It sought political rights and influence for the working classes through meetings, demonstrations and some sympathetic newspapers.

The meeting was held on the 7th December 1838 in the open space in front of the Custom House in the High Street which Hindes attended and was asked to act as chairman which he did. A number of presentations were given including one from The Rev. Nathaniel Woodard and the meeting concluded with the singing of patriotic songs, the whole proceedings were apparently carried out without any disruption or trouble.

The Meeting at the Custom House

Shortly after, Hindes was informed by the Lords of the Admiralty of the loss of his pension and was told by the Shoreham agent for the Admiralty, Henry Partington the Customs Controller, it was on account of his taking the chair at a seditious meeting held at Shoreham but that Hindes should not seek to agitate the people of Shoreham any more on the subject (there was increasing nervousness amongst those in higher places that Chartism may become out of control and violent).

Rather than taking up the cause of others John was now fighting his own corner and during the next few years much of this is recorded in letters of appeal from himself and his supporters to newspapers, sympathetic persons of influence, the Chartist Movement and even Parliament itself. The pension was not reinstated and in desperation John turned to public sympathy in an effort to set up a fund for his benefit – noticeably nothing is mentioned of John’s earlier convictions:-

To the Editor of the Northern Star

Sir, – I am a poor man borne down by oppression for my steadfastly adhering to the public cause of Chartism. I have been entirely ruined by the clergy and middle classes of Shoreham for my firm determination to uphold the cause in this Tory-ridden borough which I am sorry to say that out of a population of 1,942 by the census, cannot number but myself and two more Chartists in the strict meaning of the word.

My case is as follows:-

In December 1838 a party of respectable Chartists came to Shoreham to enlighten the people on the principles of the Charter. I being a working man was requested to take the chair, I did so; being a Greenwich out-pensioner. I was immediately reported to the Board of the Admiralty who directly stopped my pension. I memorialised them, telling them that I had done nothing wrong; when I was answered by the Secretary that their Lordships did not think it fit to restore it back to me. I answered them back that my country had given it to me for wounds received in its defence, and it ought not to be withheld from me unless I had broken the laws I had fought for; but they were determined to stop it. I then drew up a petition at the suggestion of that noble-minded patriot Mr John Frost, and got Mr T. Dunscombe to present it to the House of Commons when it was ordered to be laid on the table where it remains.

I still stood by that cause and will as long as I live. I was immediately beset by the Shoreham parsons who completely ruined me and my large family of a wife and nine children. I have dragged on a miserable existence until everything that the rascals left me is now gone. Therefore I hope through your valuable paper, the Star, the only consolation I have got, that you will be so good as through its columns to state my case to my brother Democrats throughout the Kingdom to raise a small subscription for me to buy a boat and nets that I may gain a livelihood through fishing, as I can get one for fifteen or sixteen pounds to support my family with and keep me out of the Bastille (workhouse), as that place I hope I shall never face.

If this should meet your approbation you will place me under the greatest obligation to you; and if you would act as Treasurer for me, if such a thing should take place, it will much oblige a poor but honest man.

With the greatest respect,

I am yours, in the cause

John Hindes

Shoreham, May 29th 1842.

One of the most descriptive letters of support on John’s behalf is one from Francis Hards of Surrey Street in Shoreham, again to the Northern Star, that summarises the events and background including another of his crusades and the antagonism of the clergy. Again, no mention of is made of his (Hindes’) past convictions.

Sir,- I hereby transmit to you a post office order for the sum of three shillings and sixpence, in the name of Mr. Ardill, for John Hindes who, as has before appeared in your paper, has been deprived of his hard earned pension because of his stern advocacy of right against might.

Sir, I am well acquainted with the individual in question and I believe his only crime to be that of supporting, as far as laid in his power, the poor man against his oppressors which has caused him to be a marked man by the strightbacked gentry of Shoreham. In 1834 he attacked the clergy and churchwardens of Shoreham for the unhallowed design of leveling the graves of the poor in the churchyard whose friends were not wealthy enough to erect a tombstone to point out the place where their remains were laid; and also pulling down a wall which they had thought proper to erect for the purpose of stopping an ancient footway across the churchyard. Having defeated them in this case his next crime was that of standing up against joining the Stepney(sic Steyning) Union on the atrocious New Poor Law which I believe he would have defeated had not bribery been in the camp, by making one of his partners in the struggle a relieving officer.

His next step was to hinder some of the wealthy shopocracy from taking in ground belonging to the parish, to appropriate to their own use without having obtained consent. And his battling the cause of the poor at every vestry in which he was nearly always successful, holding the straightbacks at arm’s length, until he was defeated by the Custom House minions and others by taking the chair at the meeting of the 7th December 1838 when he lost his hard earned pension. But at this he never repined until the hard times have helped the enemy to crush him and he has been completely leveled by the vermin; not only by their depriving him of his pension but also by taking every local advantage of injuring him that lay in their power: thus has a life of danger and toil been wound up by a disgraceful clergy and others.

A man , Mr. Editor, that has fought and bled for his country in the Battle of Trafalgar and with Sir Samuel Hood, off Rochfort; likewise assisting at the taking of the Isles of France, Java and Buenos Ayres; and likewise the destroying and taking of upwards of one hundred and fifty-two ships and vessels of different descriptions with other services for which this pension was granted and now in his old age to be deprived of it for standing up for his political rights as contained in that valuable document called the People’s Charter.

Should our brother democrats throughout the land be kind enough to subscribe to him the required sum he may yet hold his head up yet again. He has a large family of a wife and nine children and has, I believe, lately suffered some very severe privations and I am sure he would never have applied to the Chartists of Great Britain had it not been for the persuasions of myself and another friend to do so rather than die in a bastille as we considered him as great a victim in the cause as any. `hoping you will make his case as public as possible.

I remain,

Sir, yours in the cause

Francis Hards

Shoreham June 20th 1842

Brighton and the Last Years

Besides having relatives in Durham the Hindes family also had close ties with the Budd and Nye families in Shoreham and Brighton who in turn also had connections with Durham. John’s son Thomas married Mary Nye in Brighton and there are also occasional hints that many had Wesleyan Methodist leanings, particularly in the north east.

The Chartist movement began to lose support and with it the chances of further financial backing for John. Whether or not the collections for him amounted to enough funds to buy a boat is not known. Possibly not as it seems that John gave up on life in Shoreham, or he had hopes of better opportunities of work in Brighton as by 1851 (15) he had moved there to Cambridge Street with his wife Sarah and youngest daughter Emma. His financial situation though was still desperate. John had been in receipt of a weekly two shillings and sixpence alms payment from the Poor Law Board whilst at Brighton but this was to be discontinued and instead he was to be taken into the workhouse. John resisted this and was determined that after fighting battles for his country he ‘was not prepared to lose his liberty. ‘

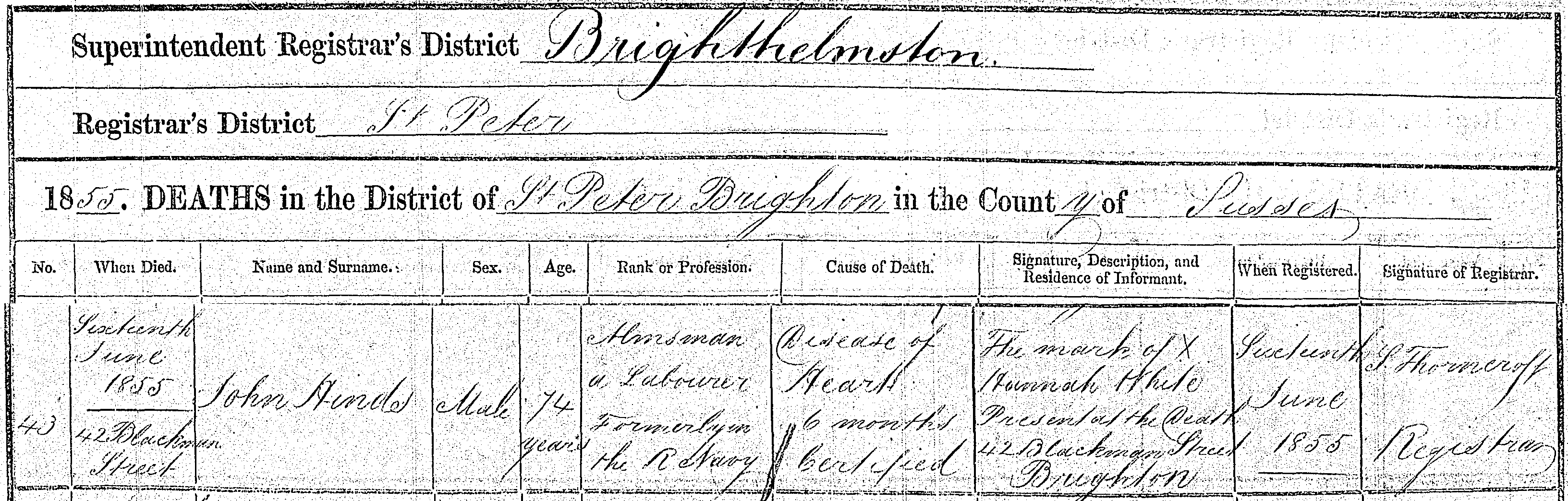

Thereafter his situation and health can only be guessed although it seemingly did not improve and after what was to be his final move to Blackman Street in Brighton he died in 1855 – whether or not he was accompanied by his wife or any of his children in his last hours is not clear but suffice it to say that the informant for the death registration was a Hannah White present at the death, not known to be a family member.

The surprise though is that John is described by the Clerk during the earlier Poor Law Board meeting as being 74 years of age, some ten years older than the age indicated by previous records – i.e., 47 when convicted in 1838; the 1841 census notes him as 49 and 60 in 1851 and now his 1855 death certificate records his age as 74. Was this a mistake or an entirely different person? Death certificates at that time were notoriously inaccurate as regards ages but reference on the certificate to his naval record and the fact his body was returned to Shoreham persuade us it was the same person.

In his plea for the alms payment to be continued he mentions his naval record again that is similar to the same record of his service in earlier reports (16). Furthermore his death certificate shows John as an almsman formerly of the Royal Navy so there is little doubt we are talking about the same person. Another clue as to the accuracy of his older age is that no possible baptisms could be found in Durham for a younger Hindes but in the non conformist records there is one for a John Hinds born on the 9th July 1780 to John and Mary in Sunderland, Durham – an age, place and non-C of E record that becomes a possibility.

John’s naval pension was never reinstated and neither was he to be given a burial at Brighton as the authorities there, wishing to avoid the expense involved, returned his body to Shoreham for burial (17).

So how do we remember John Hindes today? He served his country courageously as a Royal Marine and his efforts on behalf of Shoreham folk in preventing the graveyard leveling, resisting joining the Steyning Union and supporting the Chartist Movement are to his credit. Against this is a murky background of criminality – one was only a petty crime but the other the more serious offence of keeping a brothel. There is some doubt as to the validity of constable Butler’s evidence but most would agree that Hindes must have been aware of the activities in his own beerhouse.

Whatever our view of the man he took an active part in some of the more notable events in the history of our country and town. His sad final years of hardship and possibly loneliness can perhaps exact a little of our sympathy.

R. Bateman

Shoreham

October 2022

(1) Northern Star 2/7/1842. Battle dates – Trafalgar 1805; Rochefort in 1806; Beunos Ayres 1807; Isles of France (Mauritius) in 1810; Java 1811. In a Chartist report he was also held to have fought in the 1813 battle during the conflict with America when HMS Shannon secured a ‘glorious victory’ with the capture of USS Chesapeake at Botany Bay. There is no record of his involvement in this last battle and in fairness to him Hindes doesn’t mention it himself.

(2) ML 64 –ADM 36/16507

(3) Nine children in 1842 pp John’s letter to Northern Star May 29th 1842. These are the ones we know of according to the information below:-

Statira bap 1822 at Shoreham (Parish Records)

Sarah Matilda 1824 at Shoreham (PR’s)

John Charles 1826 at Shoreham (PR’s)

Thomas Frederick bap. 1828 at Brighton.(PR’s)

Elizabeth 1831 – 1841 census

Mary 1834 – 1841 census

Emma 1840 – 1841 census

(4) Brighton Gazette 22nd March 1838

(5) Northern Star 13th May 1839

(6) Vestry meeting of 1838 reported in the 21st August 1838 Brighton Patriot

(7) Brighton Patriot 21/8/1838, 30/4/1838

(8) Memories of a Shoreham Seafaring Family – Maria Butler, Published 2002

(9) Brighton Patriot 15th May 1838

(10) Brighton Patriot 22nd May 1838

(11) Court Report QR/W765/61 West Sussex Records

(12) George Garland collection, West Sussex Record Office ref Garland N17822

(13) https://www.gravelroots.net/petworth/prison.html

(14) September 1838 Brighton Gazette

(15) The 1851 census at Brighton shows only John, Sarah and youngest child Emma but their names and ages closely match the 1841 census ten years earlier – the remaining children were old enough to have moved out/obtained work elsewhere. However, the 1851 details show John as being born in Portsmouth. A baptism there around the possible years of John’s birth – 1775 to 1795 – cannot be traced and may simply be attributable to a lack of understanding between the census taker and John who, as an ex Royal Marine, instead of giving his birth place gave the town of his first posting, the Portsmouth Division of the Marines (See HMS Polyphemus pay book).

(16) Brighton Directors and Guardians Meeting 14th February 1854

(17) Burials in New Shoreham Parish 1855

Newspaper images reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

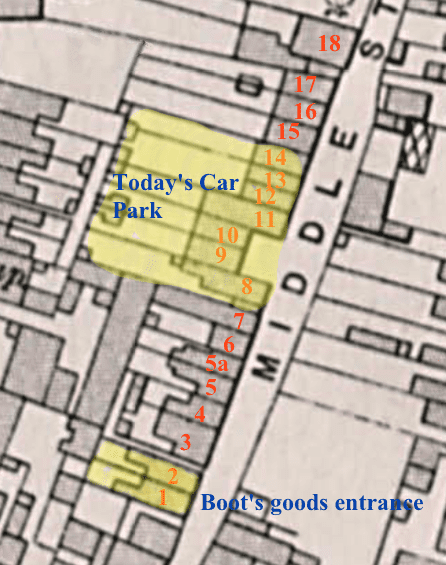

Identifying the location of the Durham Arms.

Between 1827 and 1833 the Parish Poor Rates (PPR) show John Hindes as a ratepayer living in the Tarmount area of the newly developing New Road on the east of the town but without giving a more specific location. By 1836 he is recorded in one of the Middle Street cottages that used to stand where the car park is now. In May the following year he is shown as having moved down the street to the property immediately south of and adjoining the building that was later to become the Royal Sovereign. We know this not just from the PPR’s but also by comparing the old street maps and, perhaps surprisingly, even the much later street directories.

The PPR’s that listed the contributors in each street were usually in order of occupancy from one end of each street to the other but like the Census Returns they were not always in the same or correct order. The exercise though was carried out more than once in most years and consequently if the officers of the Vestry Committee (the body that was responsible for the PPR’s) repeatedly listed the residents in the same order each time (as most of Middle Street’s were) then the accuracy of the exercises could be more relied upon.

To obtain an idea of what buildings existed during the 1830’s it helped to compare the street maps from as early as 1782 up to 1912. It became evident that most of the buildings in the 1830’s (nearly all were on the west side of the street) were still standing in 1912. Using the latter map the property numbers from the street directories of the time were then added. This provided a basis with which to identify where each resident lived.

It was found that the numbers of resident families closely matched the numbers of properties for 1836 and 1837 and where they did not it was possible to identify the reason for it. The buildings 1 & 2 were not built until after 1872 and the others south of them down to today’s Marlipins museum building were either workshops or storage and not residential. Numbers 3 & 4 (current day numbering) were one building then as were 5 & 5a but both had two separate resident families sharing them. In 1841 the latter housed no less than 25 residents as a lodging house. It was converted into two properties between 1898 and 1912 and still bears the 5 and 5a numbering that resulted. It’s earlier life as a single house is still identifiable by the one central doorway that now has two separate front doors leading off of it.

The building that later became the Royal Sovereign pub (today’s No.6) was also shared by two residents at the time. By the 1898 map it was merged into one residence but, strangely, the 1912 map shows it split again into two. By the time of the 1931 OS map though it was shown as one property again. The final street numbering must have been carried out when the Royal Sovereign was a dual property and by numbering this as 6 and 7 then continuing the numbering northwards it matches the current day surviving properties 15 to 18.