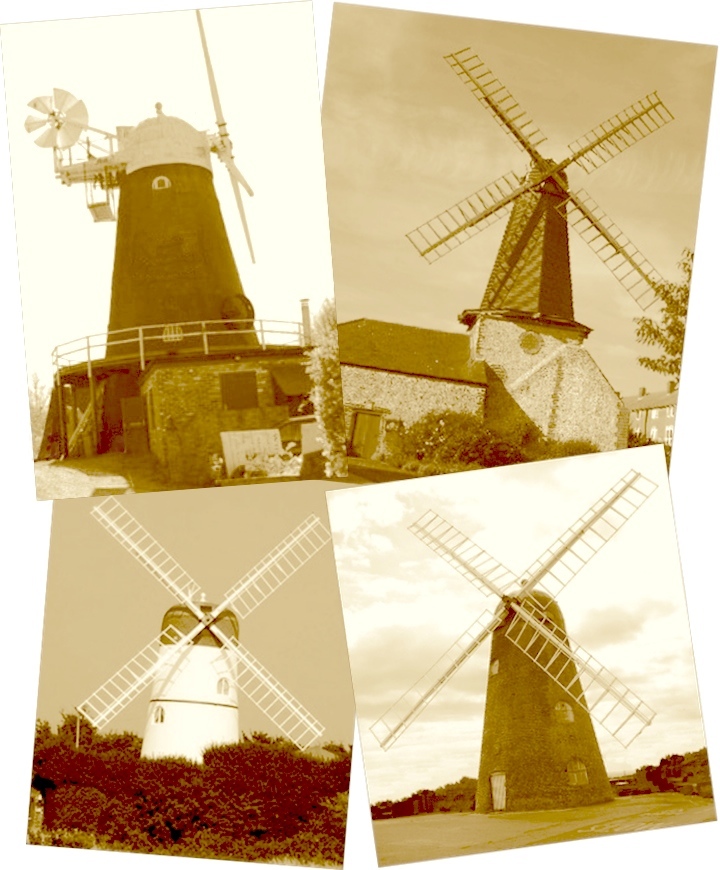

Windmills were once quite common although Sussex was perhaps home to more mills than many other counties. During the 18th century in the surrounding areas around Shoreham alone there was one each at Lancing, Beeding, and Southwick with three at Portslade if the ones at Copperas Gap and Fishersgate are included.

Little known is the fact that during the same period and into the 19th century Shoreham itself was even more populated having five, possibly six windmills in all and most of them were in the main part of town.

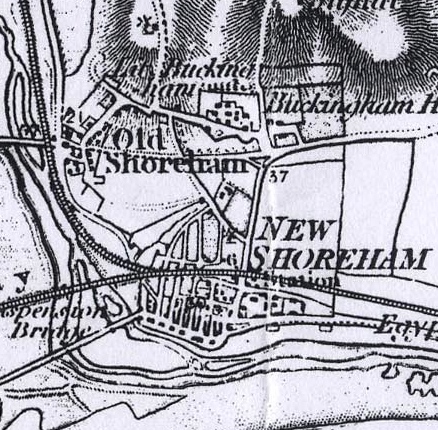

Throughout Shoreham’s mediaeval history there have been many mills but only frustratingly short references to them. There was a water mill at Little Buckingham and another near the present day cemetery lodge in Mill Lane where the water from the Northbourne Stream in those times would have had quite a considerable flow. There had been windmills at Erringham from at least 1190, the last in 1614 and another at Little Buckingham near the water mill during the 18th century. The most often used site though was on Mill Hill where windmills had been consistently but fleetingly recorded since the 14th century up to 1889 when the last mill (built in 1764) burned down.

There were two mills on the hill in the first half of the 18th century ‘bordering the old coaching road from Shoreham to Steyning.’ The last mill on the site was described as a black post mill with four white sweeps, a tail-pole and a round house built of flints that also had ‘very commodious store rooms underground’ – apparently the floor was just four feet below ground level. The 1801 Defence Schedules stated the mill was capable of supplying ‘one sack of flour every 24 hours but cannot supply wheat’ whereas another schedule recorded ’15 bushels in 24 hours.’

The first owner/miller was John Newnum who also owned a mill on Ropetackle. The second was the unfortunate George Morley who whilst working there in 1788 was hit on the head and killed by one of the revolving internal wheels. The last miller there went by the quaint name of Friend Pilbeam (previously miller at Southwick mill until it blew down) who built the cottage next to the mill in 1868. He celebrated the completion of the cottage by following an old tradition and held a ‘Rearing Feast’ after the final stage when the roof was fitted. In Friend Pilbeam’s case the meal for his guests (probably the builders) was roast beef, plum pudding and plenty of ‘good old ale’ then yet more ale at the Red Lion down the road – you can just imagine the difficulty they had climbing back up the hill after that lot!

Friend was still at the cottage when the mill alongside burned down which must have been a distressing experience for him. He died in 1899 and the cottage was demolished when the bypass was cut through.

Nearer to town the earliest known windmill was in 1672 at the west end of the High Street, probably the one on Mill Green by the riverside immediately east of the hard at Ropetackle. Mills were often rebuilt as was this one in 1715 and shown to be a post mill forty years later. The land on Mill Green included warehouses, a cottage and the windmill itself, all owned by the miller James Newnum who also worked the Old Shoreham mill as well. Following his death his widow Sarah sold the land in 1790 to Daniel Roberts who built a huge granary on it.

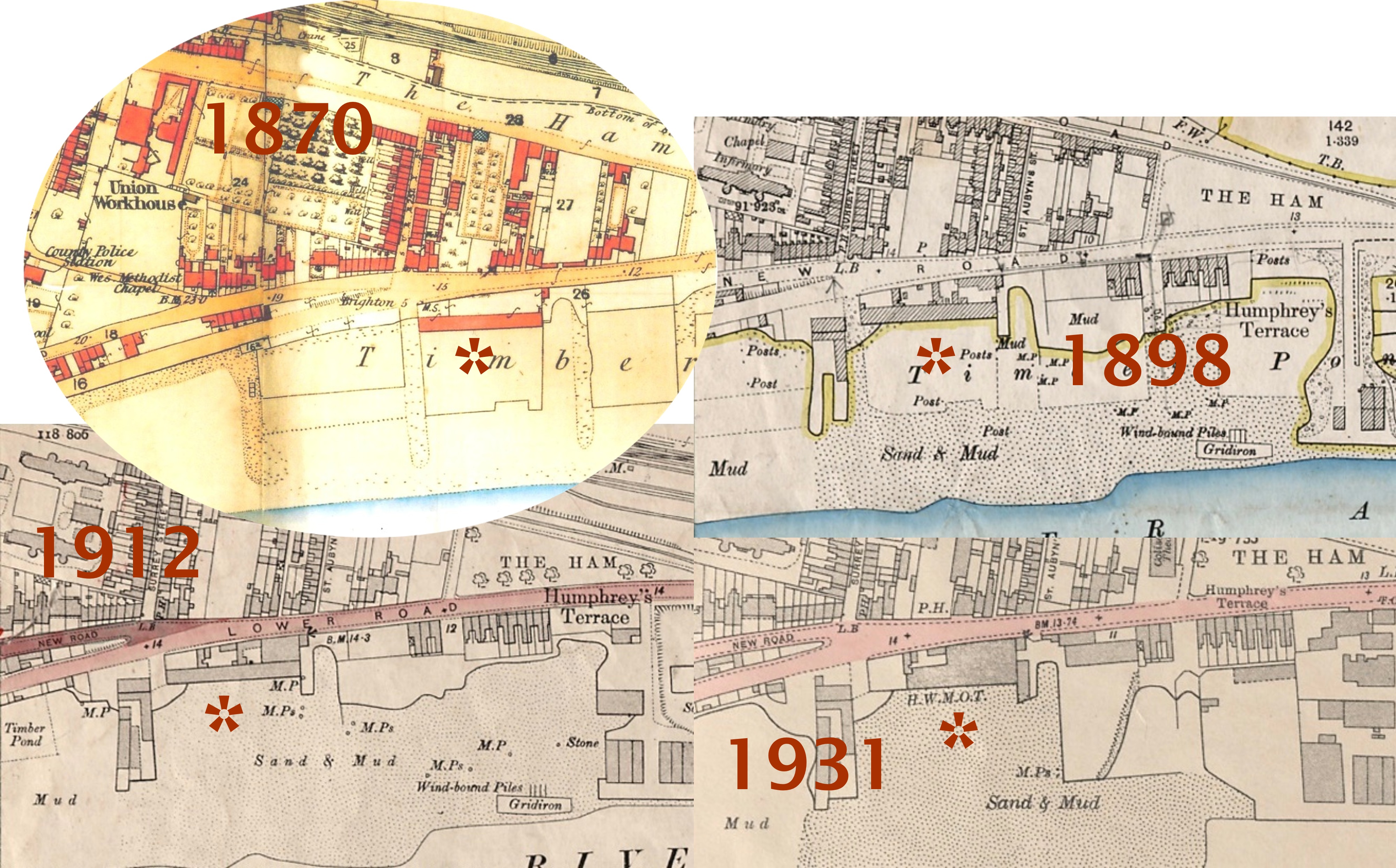

In 1809 work was carried out between Shoreham and Lancing ‘to drain the low lands in that neighbourhood.’ On the eastern side the new bank between the river and the low lying land at Mill Green extended to where the later Horsham railway line from Shoreham met the riverside. This bank can still be made out on part of the stretch north of the railway bridge where the land drops away on the east side some 7 feet in places to the now partly derelict industrial buildings and Bridges Bank residential development beyond. Most of the land has since been filled in but the old, lower levels can still be seen around the industrial buildings and the western, car park, end of the railway viaduct.

Tidal water flowed in and out of the marshland through a gap between the bank and the granary near today’s hard. The owner of the land, intending to capitalise on the situation, added further walling and in 1813 offered the Mill Green granary and resultant eleven acres for sale as being suitable for conversion ‘at easy expense to a tide mill into which a sufficient quantity of water may be let in on the flowing tide to answer the purposes intended.’

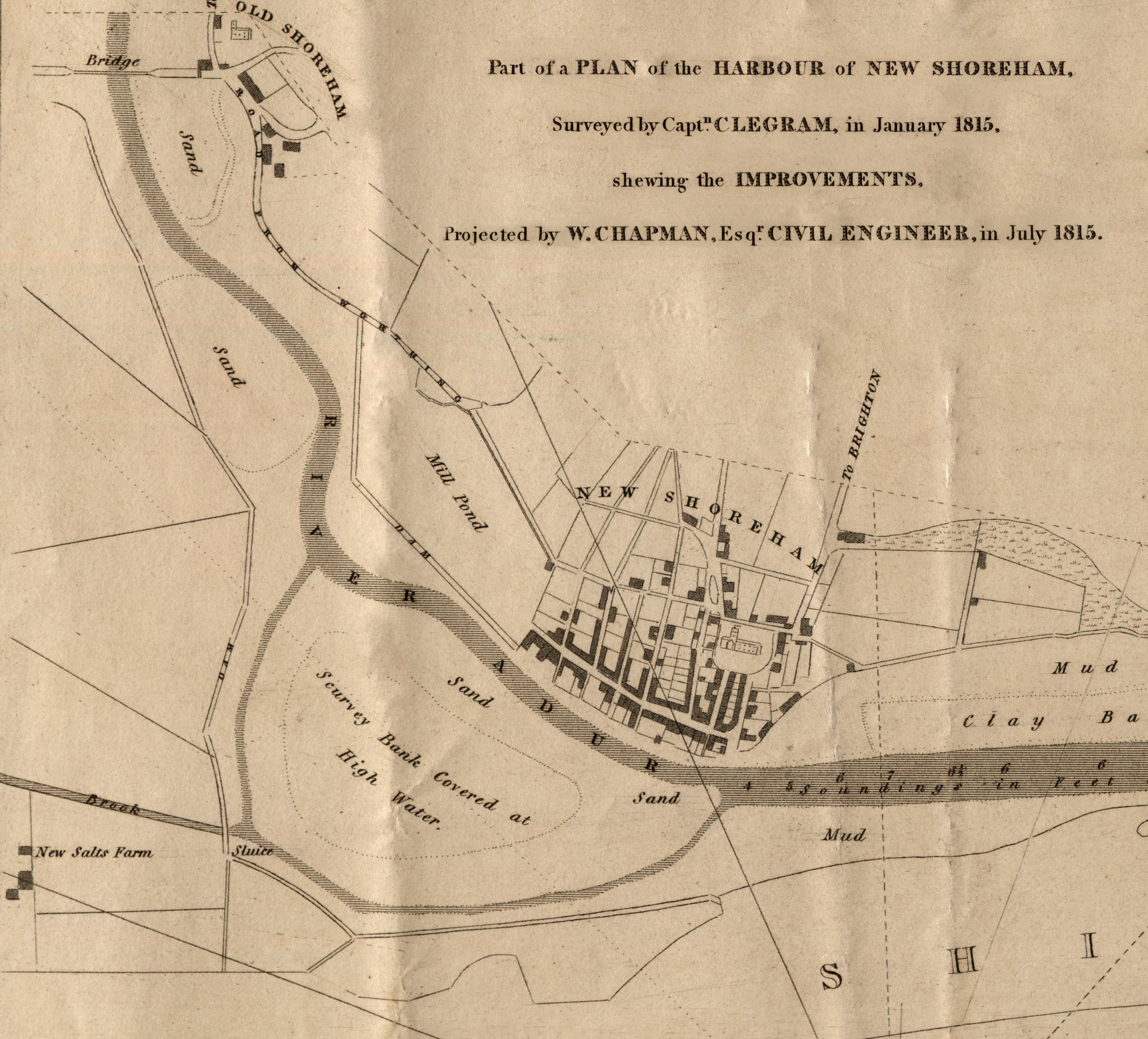

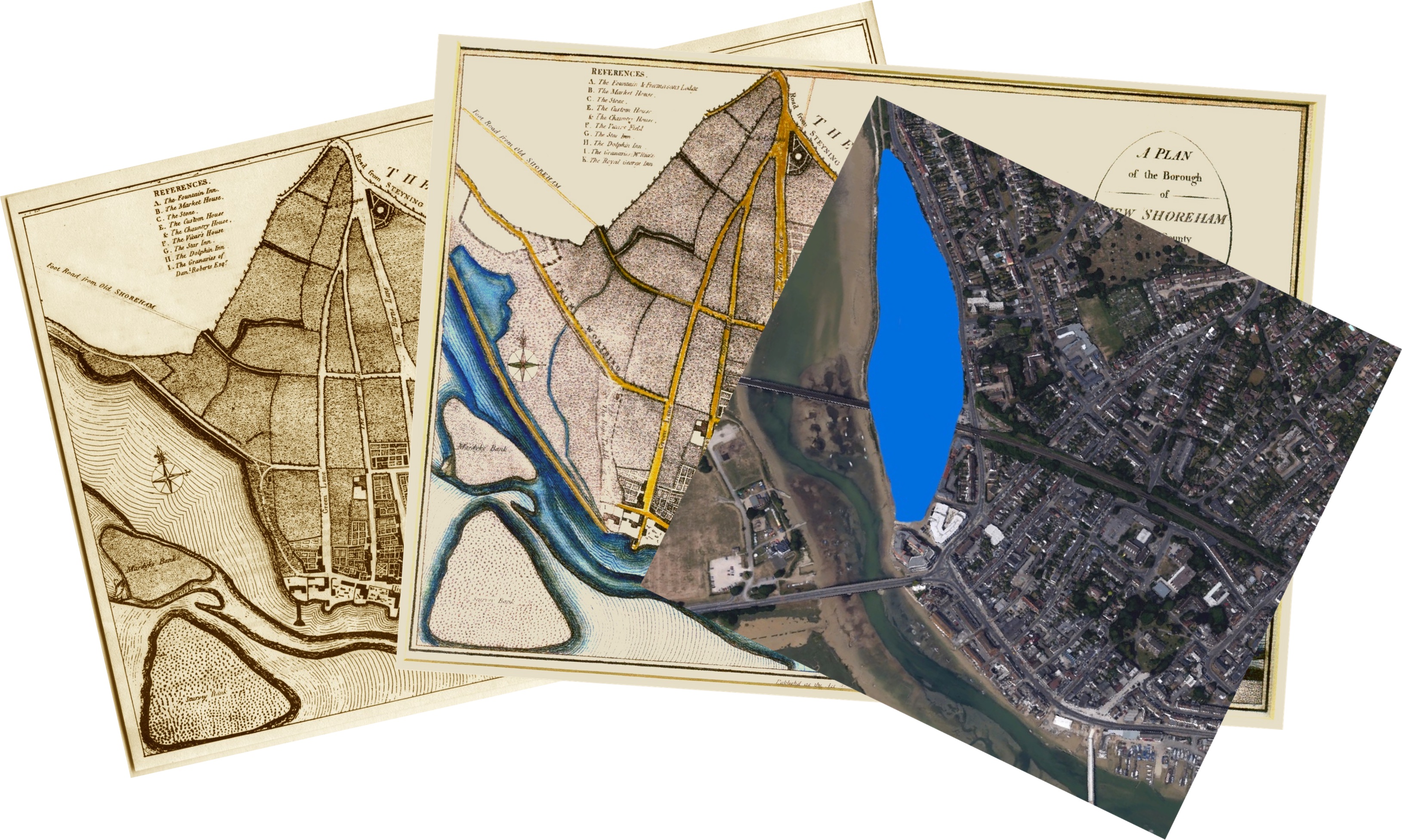

An 1815 map of the area by William Clegram (Surveyor of Works at Shoreham Harbour) clearly titles the area ‘Mill Pond’ and rather than being just a few hundred yards in diameter it turns out to have been significantly larger. The extent of the banked-in land and the water it contained was quite considerable and stretched from the hard at Ropetackle to a point just beyond where the later Horsham branch railway line from Shoreham met the river bank and in breadth from the river (bank) to the High Street/Old Shoreham Road. This meant that it not only received water from the incoming tides but also from what then still emanated from the Northbourne Stream.

Shoreham businessman John Rice may have funded the project and later Thomas Edmonds is shown in 1827 as the owner/occupier of a number of properties at Ropetackle including the Millpond. If the scheme had progressed the volume of water suggests that using incoming and outgoing tides it could have provided power for the mill wheel(s) and grinding stones for up to 20 hours a day (See notes 1 & 2). In the event it seems uncertain a tide mill was ever erected alongside the outlet to the river and it was certainly a short lived enterprise as by 1828 another of Clegram’s maps shows the granary to be missing (believed to have burned down) and the pond to have been considerably reduced to a size reaching barely up to what was later the railway viaduct and now used only as a wood bonding pond. This arrangement lasted at least up to the 1870’s when the river bank and the bonding pond’s northern boundary bank still appeared in maps of the time.

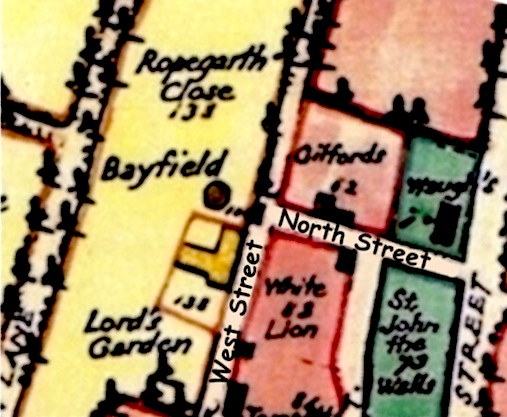

Close by, there was a further mill where the twitten between West Street and Victoria Road is now. Its footprint is shown on the 1782 Survey map and is roughly hexagonal in shape that suggests it was a smock mill. These were usually eight-sided and only three hexagonal mills survive in the country today, one of them being at nearby West Blatchington. Prior to the Survey the Shoreham mill was last mentioned as such in 1752 when it belonged to the Poole family who owned most of the land on that side of the street. The miller lived further down on the east side in the delightful period dwelling now known as ‘Ramshackle Cottage.’

It is just possible that yet another mill existed at the very northern tip of New Shoreham parish at the top of Southdown Road where the three cottages still stand today. The 1789 and 1817 maps show the cottages with a distinct windmill-like footprint or mound behind them and church records show they were once part of the chantry property recorded collectively as ‘Mylhouse.’

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries John and William Fennall had been millers at Old Shoreham windmill. William put up the mill for sale in 1829 and John continued to run his bakery in the High Street but also had another windmill built in Mill Lane, New Shoreham by Charles Best, the Steyning millwright. William died in 1830 followed by John who died two years later. The new mill was advertised for sale by the executors together with a surprisingly large number of properties that William and John had amassed between them – eighteen in all that included the Dolphin Inn with shops, a smithy, wharf and vaults in the buildings behind it, the Surrey Arms, the slaughter house next to it and numerous other building plots in the Surrey Street/Ham area – all this at a time when that part of Shoreham was being developed.

The mill was described as ‘a newly erected smock windmill with fantail, substantially built and complete in every respect together with a rich meadow field containing about 3 acres copyhold of the borough and manor of New Shoreham.’ It was painted white, had three floors above a brick base, a staging, four spring shuttered sweeps with canvas shutters and worked two pairs of stones.

It is not clear who the owner was during the years immediately following, perhaps it was rented out by the executors, but Henry Adams, a miller from Plumpton (3) who also ran a bakery in the High Street had the mill’s tenure. He enlarged the bakery by purchasing the neighbouring houses and shops from 46 High Street up to and including no.52 on the corner with John Street – the buildings are still there but much altered and still include a baker’s shop. He stored his corn in the ancient Marlipins building and also erected a large granary in John Street that still stands. He ground his grain at the new mill and the one on Mill Hill.

In 1848 there was another advertisement offering for sale ‘a capital post windmill for corn’ (the description ‘post windmill’ looks to have been an error and was replaced by ‘corn windmill’ in subsequent advertisements. Smock mills were far more efficient than post mills so it certainly would not have been converted to an inferior type) together with a plot of meadowland. Adjoining was another meadow of 2 acres 1 rod and 10 perches called Mill Field all in the tenure or occupation of Henry Adams. The size of the plot and field combined brings us close to the three acres mentioned for the smock mill.

It seems that this was when Henry finally purchased the mill for himself. He must also have been well aware of Shoreham’s growth as new housing spread northwards, particularly that planned for Queen’s Place, all of which obstructed and reduced the effectiveness of the wind upon the sails. The wind-power at the mill had by then been supplemented by a portable engine in any case but perhaps it was at this time that it was rebuilt as a steam powered brick tower mill.

Millers often worked more than one mill as Friend Pilbeam from Old Shoreham then John Dennis were employed to work it – Pilbeam is known to have worked four different mills. Henry died in 1854 and was succeeded by his son, also Henry. Having been enriched by the majority of his father’s estate he invested in the shipping business becoming a ship owner himself and in 1880 at the age of 50, married 24 year-old Ada Gates. In doing so Henry not only gained a young wife but also married into what was one of the largest ship owning families in the area.

Henry junior does not seem to have shared his father’s enthusiasm for the work and in 1866 he put the bakery and milling business up for sale but in the event seems to have retained ownership of the mill. Master miller Henry Muggeridge from nearby Queens Place became the last tenant in 1890 but at eleven o’clock on the night of the 14th January the following year Henry M discovered a fire in a room above the engine house. The Shoreham Fire Brigade soon doused the flames but the mill doesn’t seem to have been much used after that.

In 1900 the Adams family moved into the appropriately named ‘Mill House’ that Henry had built next to the mill in Mill Lane. The architect’s original coloured drawings of the house and mill can still be seen in Adur Council’s Planning Department. The mill was demolished shortly after. Henry died on 14th October 1916 at the good age of 86 and is buried in the Municipal Cemetery.

With windmills came millwrights to build and service the mills. Originally the moving parts were made of wood but the industrial revolution brought more efficient metal mechanisms and the millwright’s job was transformed. During the early 19th century machine makers J & J Rawlings from Strood in Kent opened their works in Shoreham, managed it seems by Joseph Rawlings, millwright, who lived in the High Street. In an 1811 advertisement for their winnowing, chaffing and sowing machines and even mangles the firm boasted having made over 600 different types of machine. In 1825 Rawlings of Shoreham were shown as manufacturing a threshing machine claimed to have been ‘built upon the most approved principles of improvement.’ A second hand model was advertised for sale as being ‘without exception one of the best in the county.’

We know little of the firm’s success or otherwise as millwrights but John Britten Balley the shipbuilder was Joseph’s next door neighbour so he was likely to have had work on machinery for the shipyard as well as that which he did for agricultural purposes. However nothing more is known of the Rawlings and they appear to have ceased trading in the town after the 1840’s.

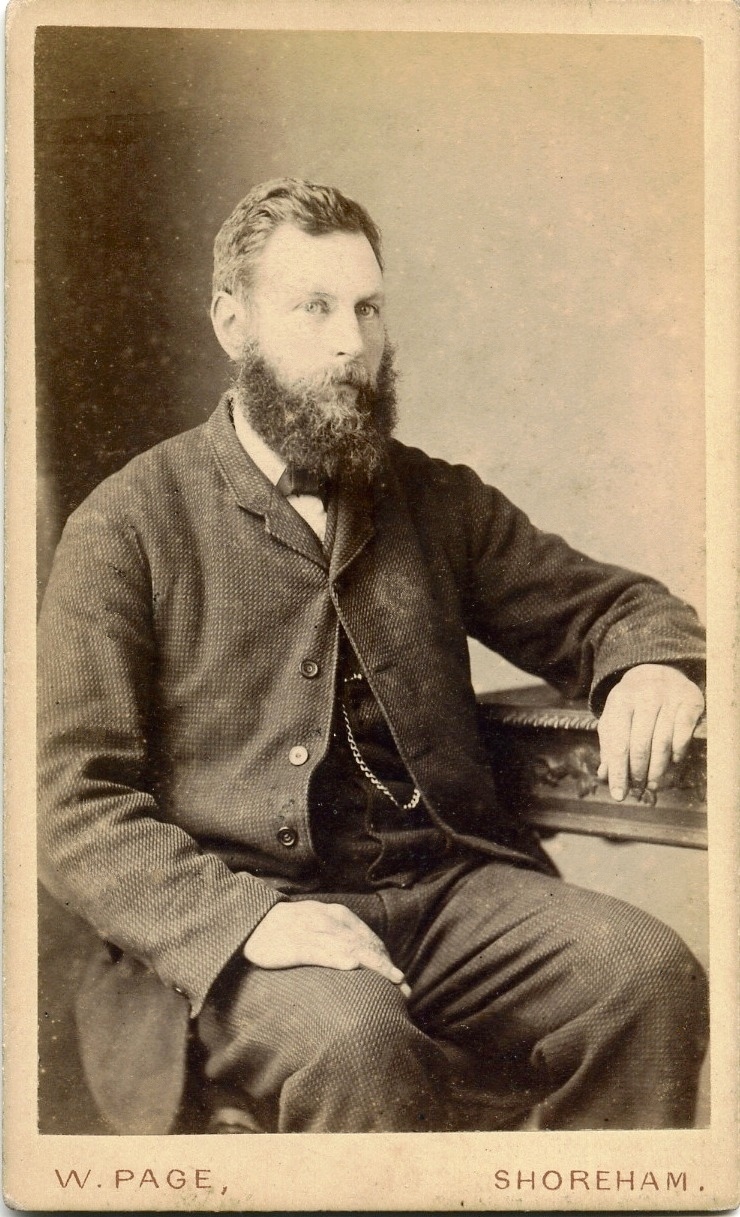

A later Shoreham millwright though was particularly successful. James Walter Holloway first came to Sussex in the 1850’s when his father, a Brockenhurst butcher, was appointed for reasons unknown as the police superintendent for Steyning – something of a career change! James’ interests though were in the field of mill machine engineering as he came of age possibly as an apprentice for another millwright that lived near him in Charlton Road.

James started the company of Holloways Engineers Ltd in 1863 and rented premises in and behind the ancient building that was later to become Marlipins Museum. His tooling machines were driven by one stationery engine which must have presented something of a considerable fire risk as the buildings, particularly the ones behind in Middle Street, were constructed largely of wood.

It seems the noise, smoke and smells from the works were not popular with the neighbours and after numerous complaints the firm were moved out of Marlipins during the late 1870’s. The premises there were in any case not the best place for an engineering works and didn’t allow much scope for expansion but James found an ideal replacement on the Lower (Brighton) Road; a large site consisting of ‘a yard, offices and eastern loft, lower yard, two workshops, a further loft and three ponds.’ The ponds were for floating new timber to prevent it drying out used for repairing the wooden parts of mills. This was all on the south side of the Brighton Road where Frosts showrooms are now with its main entrance opposite the Duke of Wellington pub.

It is hard to imagine that he did not work on the Old Shoreham and Mill Lane mills but there is no known record of it. One of the earliest and more unusual jobs we do know of was in 1881 when James, by then already using (and perhaps making) traction engines, came to the rescue of a stranded windmill! It was not unusual for windmills, despite their size, to be moved from one site to another. The build up of houses around Worthing’s Cross Street mill had reduced the effectiveness of the wind on the mill’s sails and it was decided to move it to the east near Brooklands. A team of 40 horses had successfully hauled it as far as the Anchor Inn on the corner of Lyndhurst Road but the tight turn there meant that the combined pulling power of the whole team was no longer effective and it became stuck. It seems James Holloway’s traction engines were the nearest available solution as he was summoned and just two of his machines completed the task.

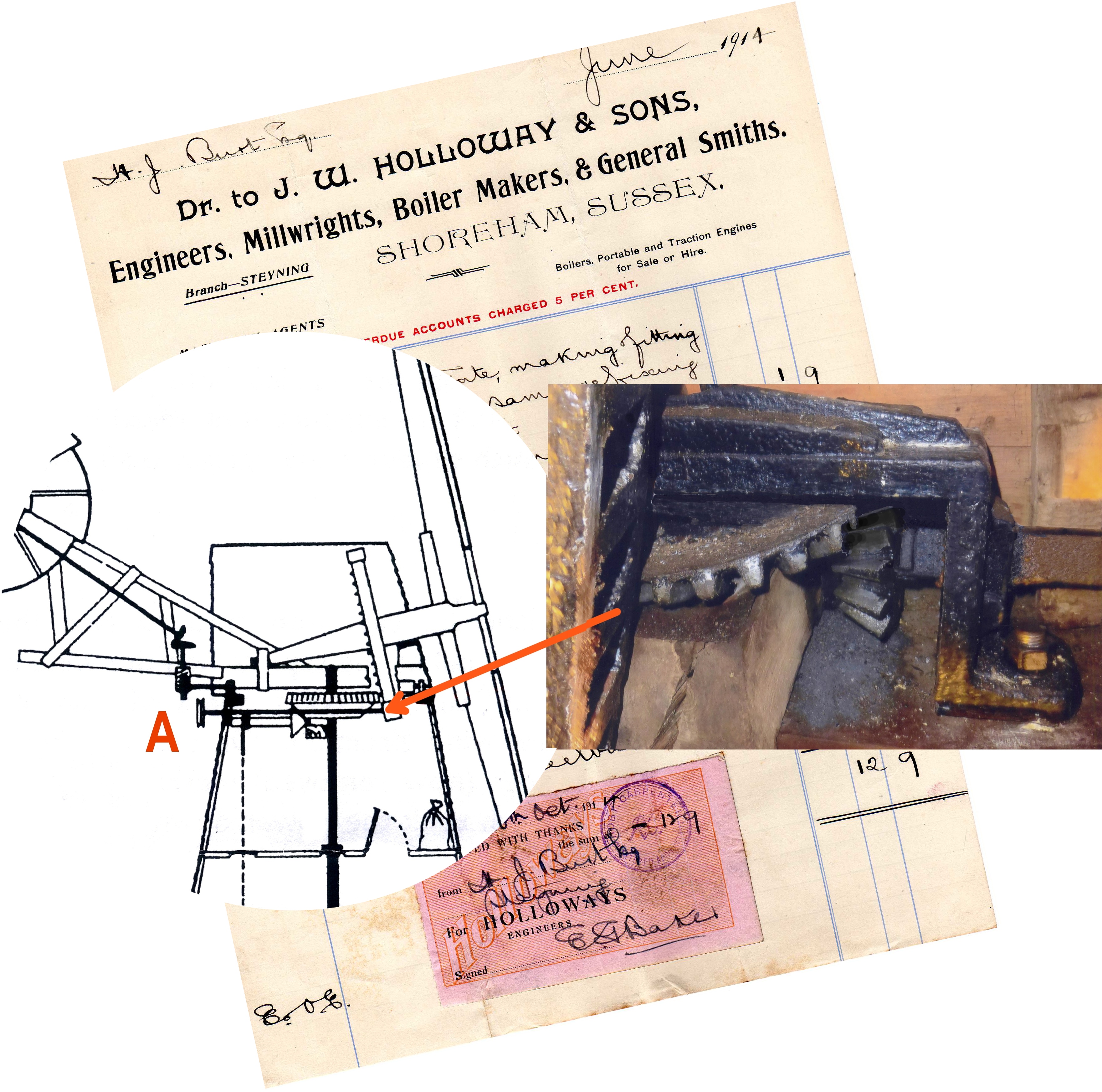

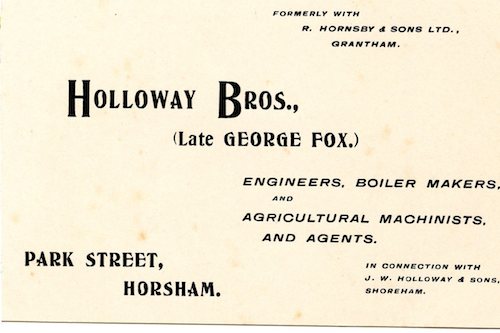

Of other the work he carried out on wind and water mills some of the more important jobs were the fitting out of the newly built Patcham windmill (1884/5), converting Barnham mill, adding a steam engine to supplement the wind power (1890) and refitting Selsey mill (1908) after the firm had become Holloway Brothers. These and West Blatchington mill still house James’ machinery bearing the name ‘HOLLOWAY ENGINEER SHOREHAM.’ A particular innovation for which Holloways became well known was their screw brake. This enabled a gradual slowing down of the sails rather than the traditional lever and weight – examples still survive at West Blatchington and Barnham mills.

It is interesting to note that Friend Pilbeam, the miller of the Old Shoreham mill, was also employed at Holloways’ yard to operate the steam mill there. He had worked Southwick mill before it blew down, Old Shoreham of course, and the Adams’ mill in Mill Lane

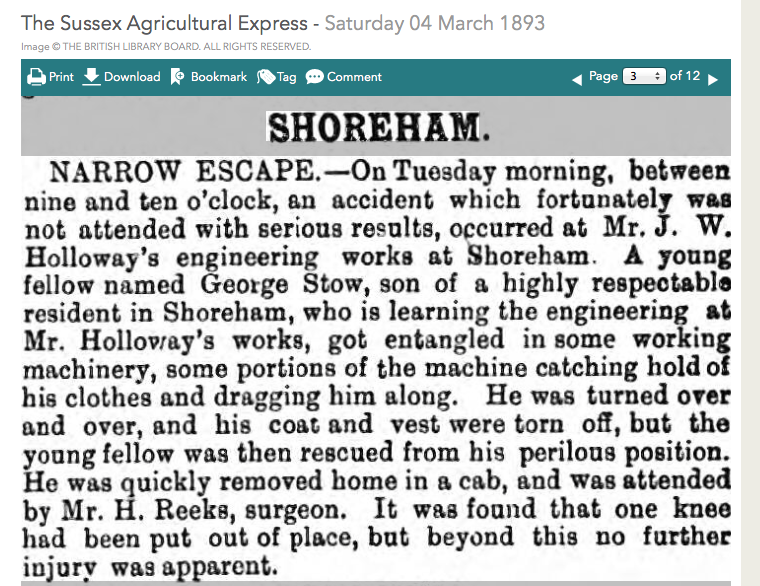

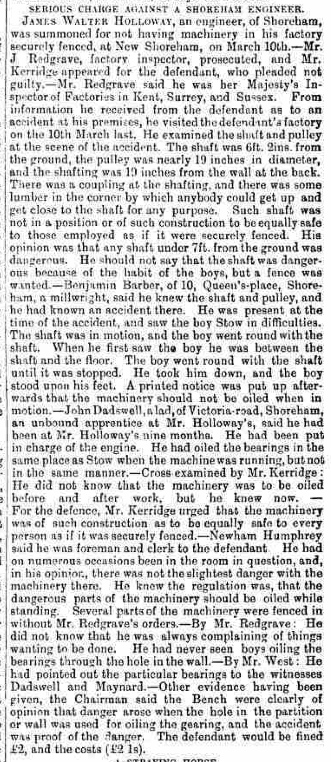

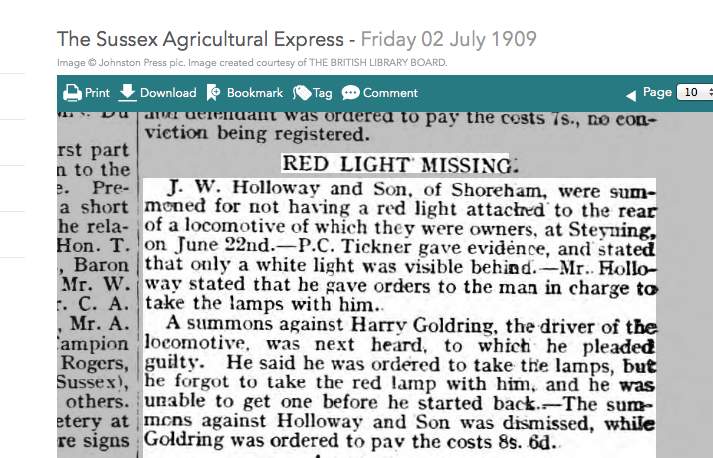

Life at Holloways was not without its drawbacks though and in 1893 James was summoned to appear in court to answer a charge of having machinery at the factory insufficiently fenced off. George Stow, an apprentice and son of Thomas, Shoreham’s celebrated yacht builder, had become entangled in the revolving shaft of an engine whilst endeavouring to oil the bearings in it resulting in a dislocated knee and torn clothes. It seems that even though the boy should not have carried out the task until the shaft was no longer in motion, James was nevertheless fined £2 with £2.1s 0d costs. Another incident in 1909 involved one of the firm’s locomotives at Steyning that had been travelling without a red light attached to the rear of the machine. The driver, Harry Goldring, was ultimately prosecuted and fined 8s/6d for the offence but it would be intriguing to know just what that ‘locomotive’ was?

Millwork would not have been a regular source of income but James was successful in diversifying his engineering business. He bought, sold, repaired and hired out agricultural machinery; made steam, gas and oil engines, boilers; manufactured and maintained machines for hospitals and factories, parts for tractors and steamrollers, mowers and general smithing.

Business grew, extra staff were taken on and by the 1890’s there were 30 to 40 employees at Shoreham with other works being opened at Charlton Road and Market Place in Steyning.

It is hard to imagine that he did not work on Old Shoreham and Mill Lane mills but there is no known record of it. One of the earliest mills he did work on was at Rustington where he met the miller’s daughter Harriet Humphrey. They married in 1867 setting up home in Brunswick Road, Shoreham. Incidentally, in 1871 Harriett’s brother James Humphrey acquired the creek and land opposite today’s Brighton Road junction with Eastern Avenue, built the terrace on the east side of the creek and three so called ‘villas’ on the west side (really another terrace of three houses) then rented them out. James Holloway and his family moved to one of the villas in the 1890’s. The area of course became known as Humphrey’s Gap and whilst the terrace has since been demolished the villas still stand albeit their future may now seem questionable.

James was not to enjoy a particularly long life and died in 1905 at the age of 63. He was successful in developing and diversifying the engineering business in Shoreham but is best remembered for his mill work throughout Sussex and remains widely recognised by mill historians today.

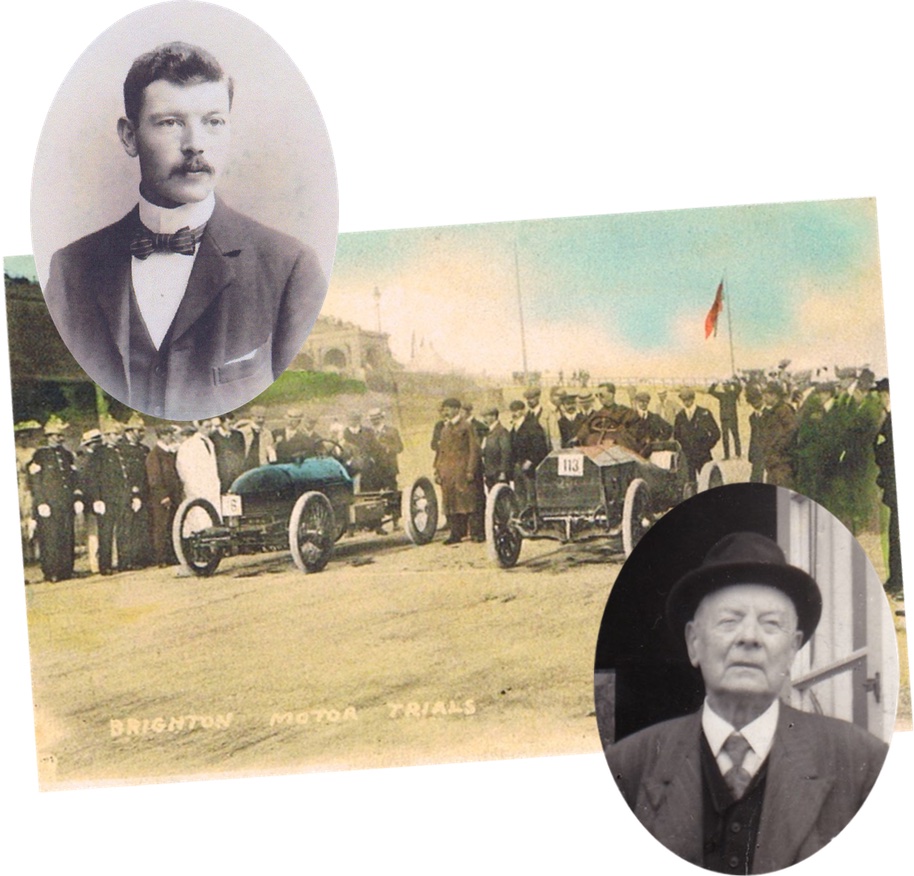

James and Harriett had six children and of these, sons Albert and Fred were to follow their father into the engineering business. To ensure a continuation in the management of the necessary skills James had trained Albert and Frederick in apprenticeships as fitters, turners and millwrights. Albert had also spent time with another firm working on engines and boilers around the country as well as a couple of years setting up plant and machinery at a goldmine in British Guiana. Frederick’s main interest was in cars and he took part in the early speed trials that were held on Brighton seafront. Doubtless it was partly due to his enthusiasm for this that led to the firm becoming more involved in motorised vehicles.

Holloway and Sons were specialists in engines of many types but ironically it was these engines that were taking over the work previously carried out by the wind driven mills. Subsequently the millwright side of the firm’s work died away during the early 1900’s but under the guidance of the two brothers the earlier diversification and development of the motor and garage side of the business ensured its continued financial stability.

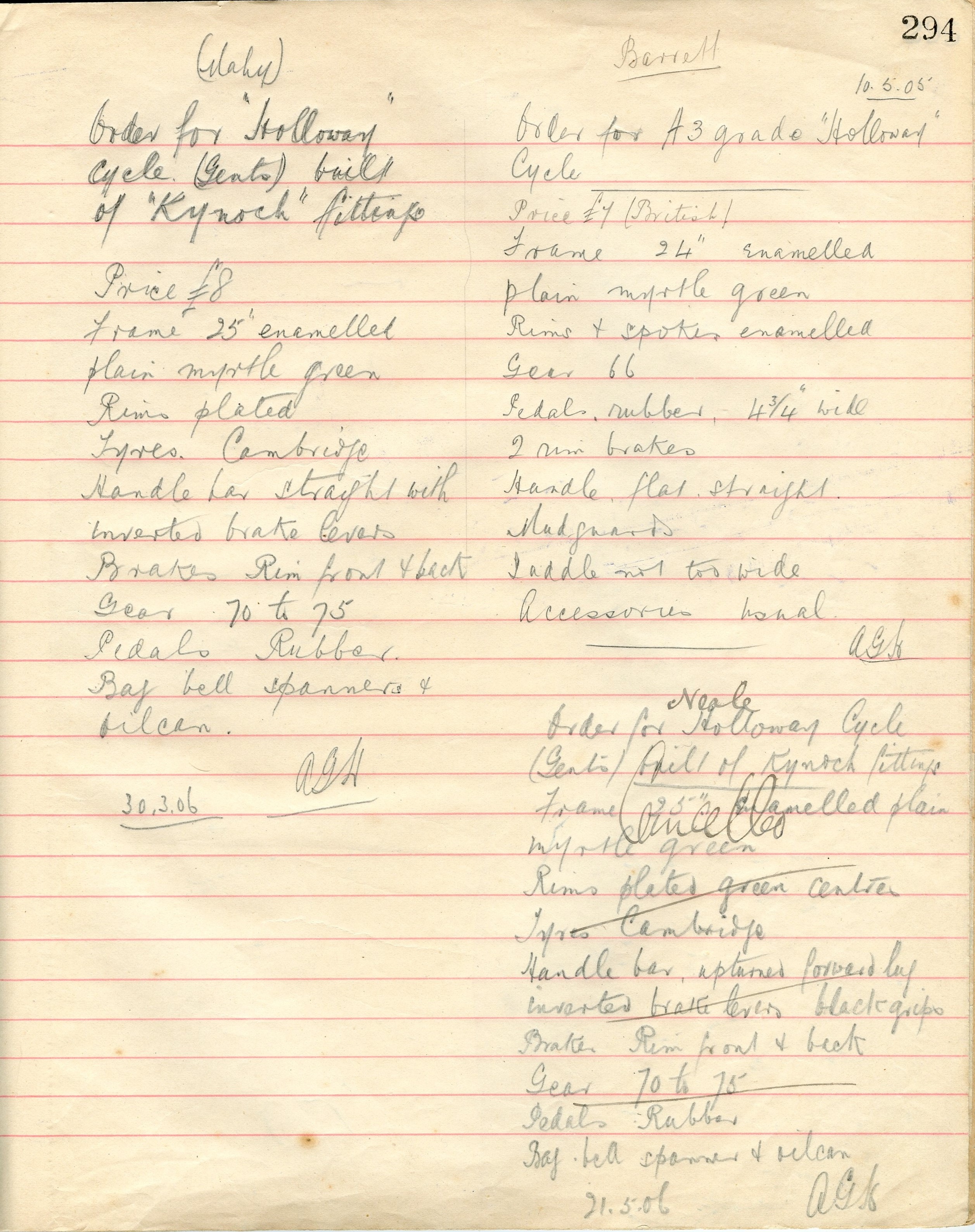

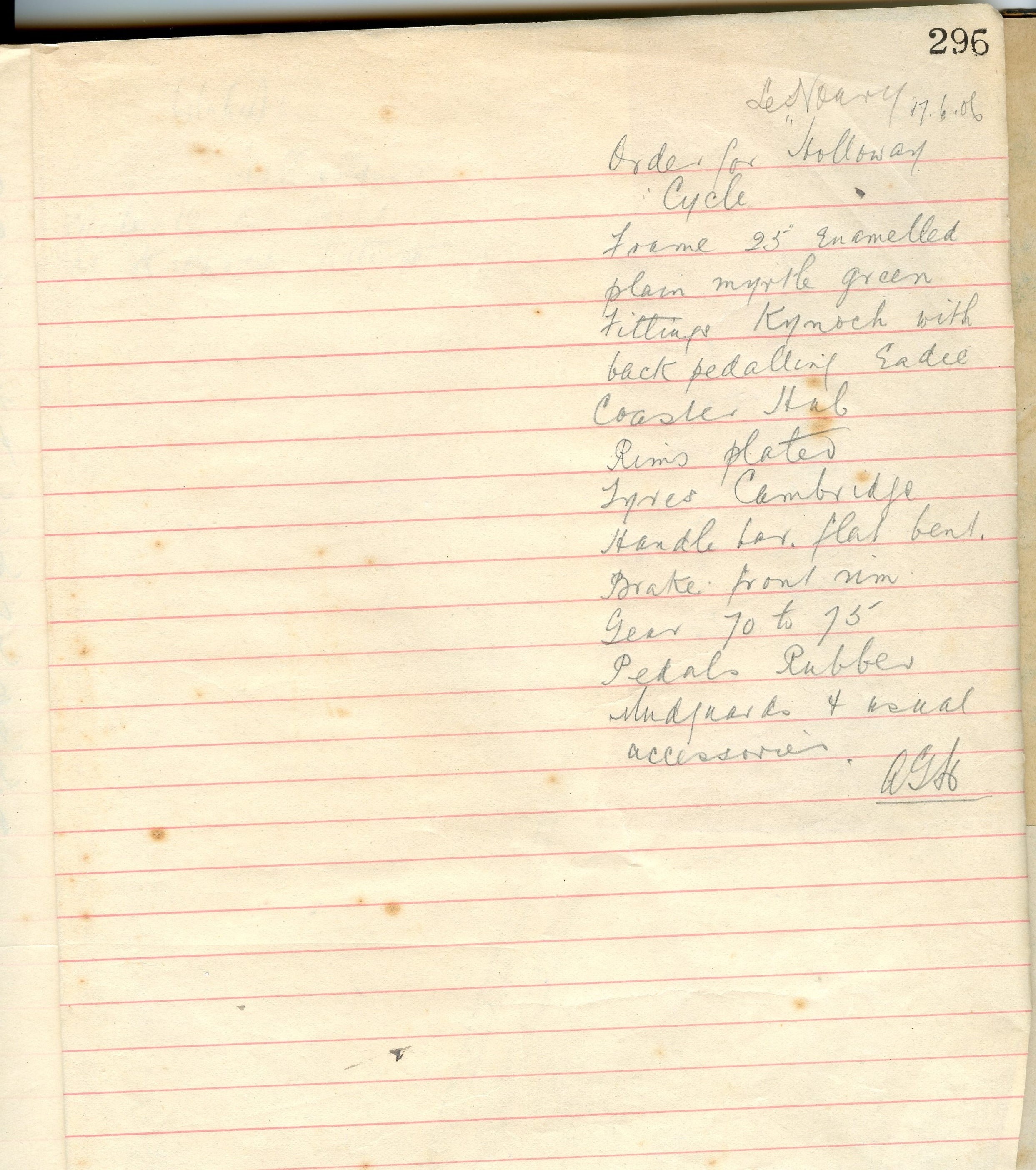

Whilst father and sons had been still working together the firm were making bicycles. Mens’ and ladies’ versions were sold for a little over £12 each although the ladies’ at least had the option of more expensive fittings at a total cost of £14! One bicycle in particular was the Holloway A1 – a substantial twin-crossbar machine. A 1903 example survives to this day previously owned by a Holloway descendant but now given a new home at Shoreham’s Marlipins Museum.

Next came motorcycles with Holloways producing the frames and assembling the bikes using am ingenious Belgian Minerva 2½ hp (239cc) ‘clip-on’ engine and fuel tank. Another surviving gem is a handwritten 1903 quotation for a ‘Holloway Motor Bicycle’ costing £41 that includes hire purchase terms requiring an initial payment of £10 cash, twelve monthly instalments of £2.10s monthly and a final payment of £1 to be made on January the 1st 1905!

Perhaps the loss of competition following the 1911 closure of Ricardo’s ‘Two Stroke Engine Company Ltd ’ car factory in the High Street had encouraged Holloways to promote their own vehicles as their directory entry that year states they were ‘motor car and motor cycle makers.’ There is no record of a complete Holloway car being made though but they had thriving agencies, at first for Buick and Vulcan makes and by the 1950’s and 60’s they were to be main agents for Austin/Morris (BMC), Hillman, and Standard Triumph.

One of the most unusual projects that the Holloway brothers were to deal with has to be the 1912 motorised street cleaning machine that they made for the Belfast City Council. A photograph of it was taken before (presumably) the bodywork was added making it look a wonderfully bizarre looking contraption more typical of the impossibly quirky machines thought up by earlier Victorian inventors.

After Fred and Albert the business passed to Albert’s son Leonard (in charge of the engineering business) together with Fred (who looked after the car dealership) and Reg (car workshop foreman) the two sons of Florence Knight (nee Holloway) and in addition to the engineering work the motor sales, repairs and maintenance business flourished.

The firm had been involved in many different projects of all sizes from the 1883 repair of Angmering church bells for example to the Shoreham harbour reclamation work in 1925. The main source of income though on the engineering side came from steel welding, boiler and pipework and two of the more notable customers were Brighton Pier for the frequent replacement of the pier’s rusted and damaged parts, and Southlands and Worthing Hospitals for the maintenance of the boiler and pipework there. During WW2 Holloways made anti-tank gun mountings and parts of the steelwork for the D-Day Mulberry Harbour – the work for the latter was so secret that at the time of carrying out the work they had no idea how the parts they were making were to be used. Demand was such during the war years that the factory was often kept going 24 hours a day.

Perhaps the firm’s biggest customer over the years was the Shoreham Cement Works that, with its considerable machinery, had grown massively during the 20th century. There is a photograph of a huge stone crusher on a lorry outside of Holloways Brighton Road works during the 1950’s that had been lifted on to the lorry by two large mobile cranes. The lorry and cranes were then driven in convoy under police escort to the Cement Works’ clay quarry in Small Dole – an impressive undertaking in those days when such heavy machine transportation was rarely seen.

Another unusual project at that time was when Holloways built a lorry for Ready Mix Concrete Limited that included the revolving cement drum and was finished in RMC’s bright orange colour. Leonard Holloway was later to hold that his firm built the very first mobile ready mixed cement lorry in the UK and although this cannot be verified it was without doubt cutting edge engineering technology at the time.

By the early 1970’s the financial ownership of the firm had become fragmented between many family members with ageing directors and no obvious successors to take their place. As it happened, at that particular time the proposed Brighton Road development scheme triggered a compulsory purchase order of the Holloway site. The situation as it was engendered little enthusiasm amongst the owners nor the means to continue the business elsewhere and in 1973 Holloways one hundred year association with Shoreham finally ended.

(A small collection of Holloway bicycle specifications, patent purchases etc., follows in the appendix at the end of this article)

Roger Bateman

Shoreham

June 2014 (updated February 2015)

Notes:-

1. Overlaying the 1815 map on to a modern Ordnance Survey map the distance from Ropetackle Hard to the northern tip of the water catchment was about 1200 feet long by 400 feet wide, or 480,000 square feet equivalent to almost exactly the 11 acres mentioned in the 1813 advertisement!

2. That part of the bank beyond the railway bridge drops some 7 or 8 feet in places on the east side, well below the high tide mark. Water in the west half of the pond must have been at least 4 feet deep even though the land gradually rises on the eastern side some of which may have been little more than flooded marshland. An internationally accepted measure of 1 acre of water at 1 foot deep is 43,560 cubic feet. Half of the 11 acres = 5.5 x 4 x 43,560 = 958,320 cubic feet. Assuming the other half was no more than one foot in depth there was 43,560 cubic feet x 5.5 = 239,580 cubic feet. The total 1,197,900 cubic feet of water at high tide or 7.46 million gallons.

3. See also the article ‘Farmers, Millers and Bakers.’

18th and 19th century owners/millers and year of record:-

Mill Hill, Old Shoreham – Richard Ashby 1761; James Newnum 1787; George Morley 1788; William Badcock 1792; Joseph Tillstone (ropemaker at New Shoreham) 1796; Mr. Slatter 1799; William Fennall 1823 – 1829; James Trusler 1838, Friend Pilbeam 1882 – 1895 (he had also worked the windmill at Southwick and the steam mills at Mill Lane and Holloways’ Yard).

Mill Lane, New Shoreham – Owner John Fennall 1832; Miller Henry Adams senior 1832 – 1854; owner Henry Adams junior 1855 – 1900; millers Friend Pilbeam and John Dennis circa 1860 to 1889; Henry Muggeridge 1890.

Special thanks to Brian Roote; Chris Tod, curator, Steyning Museum Trust; Peter Hill of the Sussex Mills Group and especially Holloway descendants Pat Dawson, Brian Holloway and Julian Knight for their stories and photos of the family and business.

Other Sources

1782 Survey of Shoreham

British Library Newspaper Archives

‘The Story of Shoreham’ by Henry Cheal

‘A Walkabout Guide to Shoreham’ by Michael Norman.

British History On Line.

1774 to 1832 Poll Books & Directories

Parish Transcripts

Parish Poor Rates

Census returns

Simmons Collection of records relating to British Windmills and Watermills compiled by H.E.S. Simmons held by the Science Museum Library, London.

Engines & Enterprise by John Reynolds

West Sussex Archives – Vestry Minutes Par/6/12/2

National Archives – Shoreham Harbour Reclamation Works BT 356/9516

(Appendix follows on next page)

Appendix – Holloway bicycle specifications, hire purchase agreement, 1905 Bicycle Secifications etc

Receipt for the Holloway Bicycle 1903 sold to Alfred Jenkins

1903 motor cycle hire purchase agreement

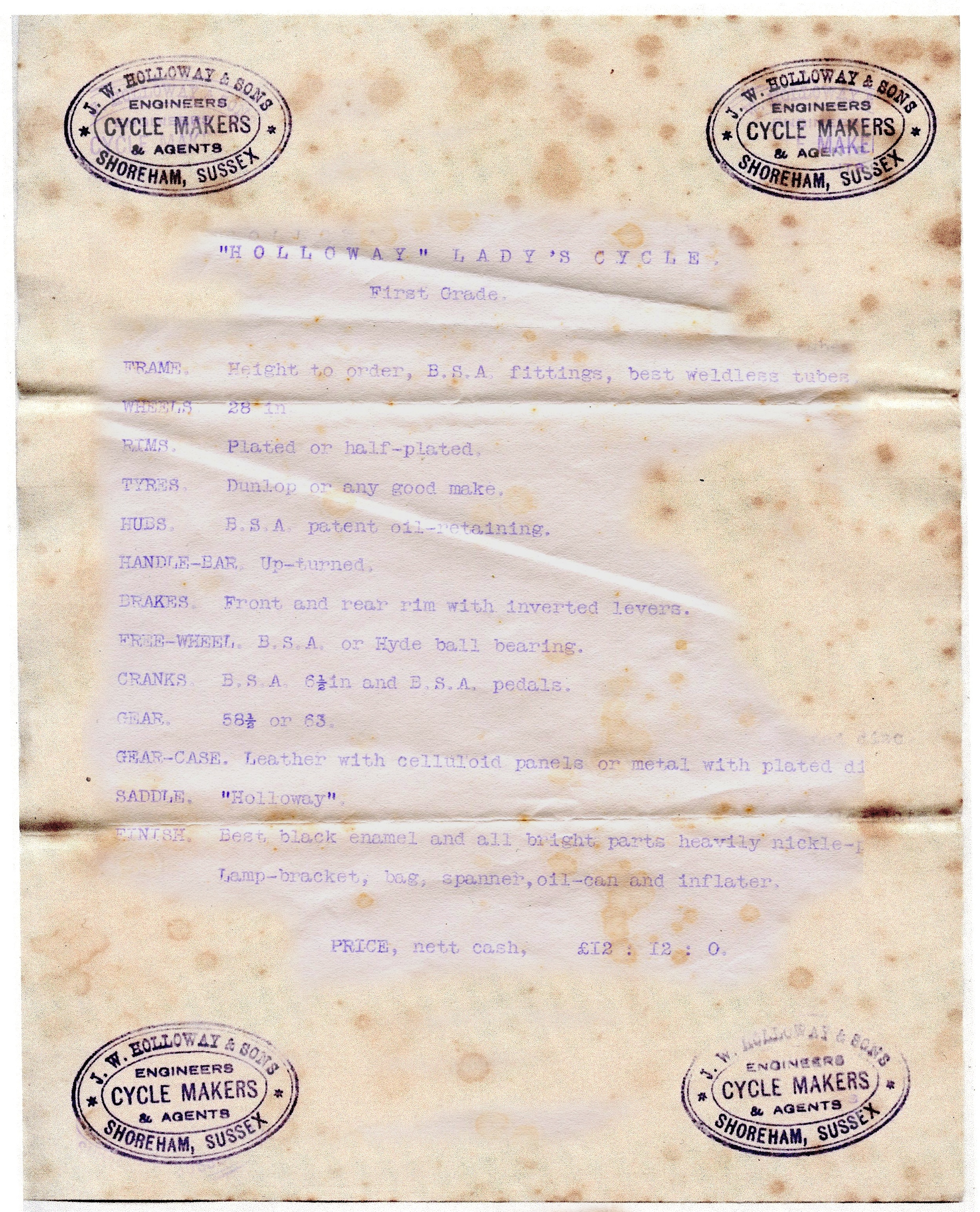

Early 1900’s Lady’s Bicycle Quotation (faded typing enhanced to make readable)

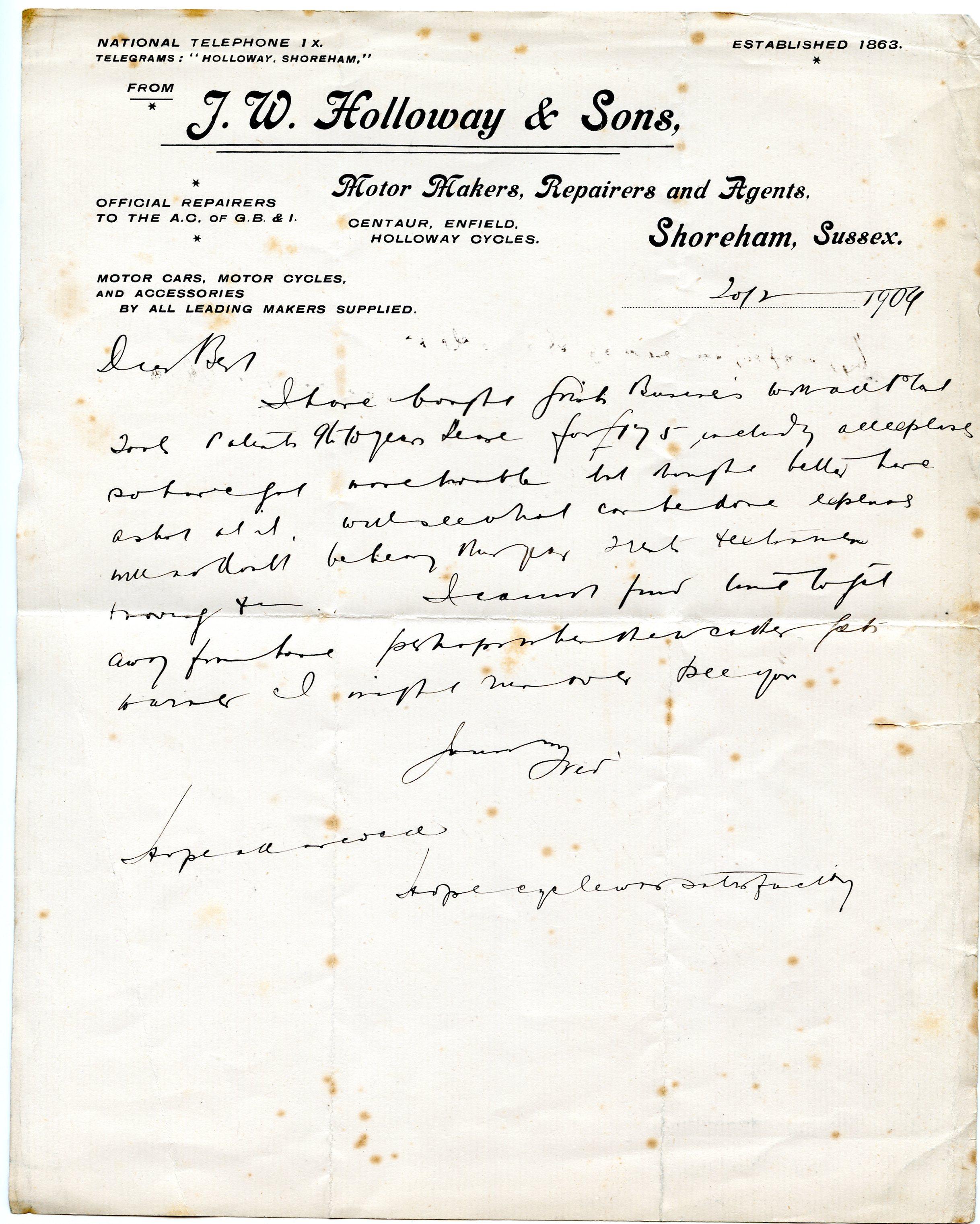

1909 patents purchase

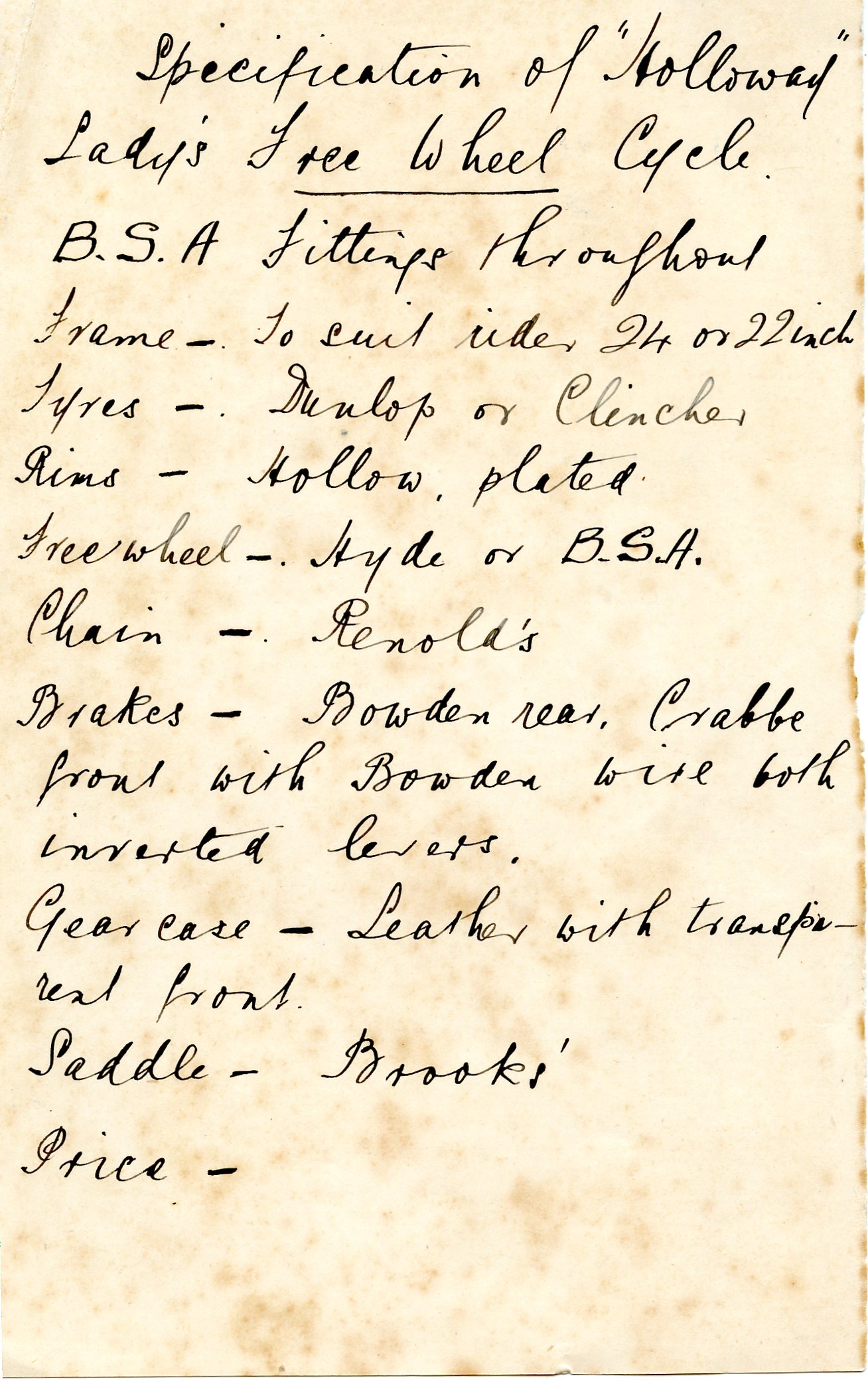

Early 1900’s Lady’s Bicycle Specification (1)

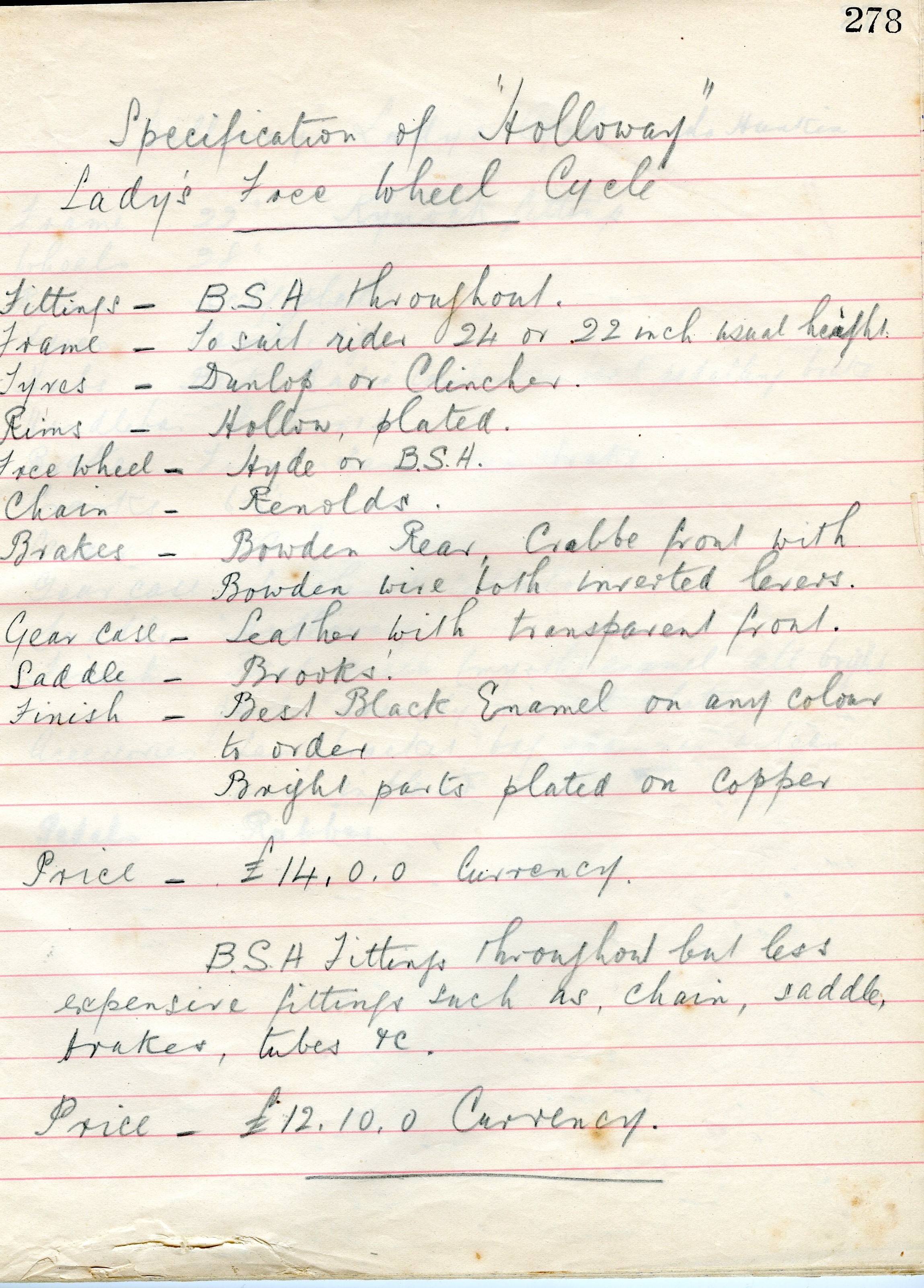

Early 1900’s Lady’s Bicycle Specification (2)

1905 Bicycle Secifications

History of the Holloways works site to 1910:-

1830 to 1861 The Buckwell family, timber merchants, owned and used the timber yard, buildings, timber ponds and creek.

1871 Charles Cork rented the yard, office and coal store there (Cork probably built Cork Cottages in New Road). William Hampton was the owner of that and the creek and used an office there for his insurance business.

1881 to 1910 Holloway occupier – Mrs Hampton owner

Sussex Express 29th April 1893

One Reply to “Mills, Millers & Millwrights”