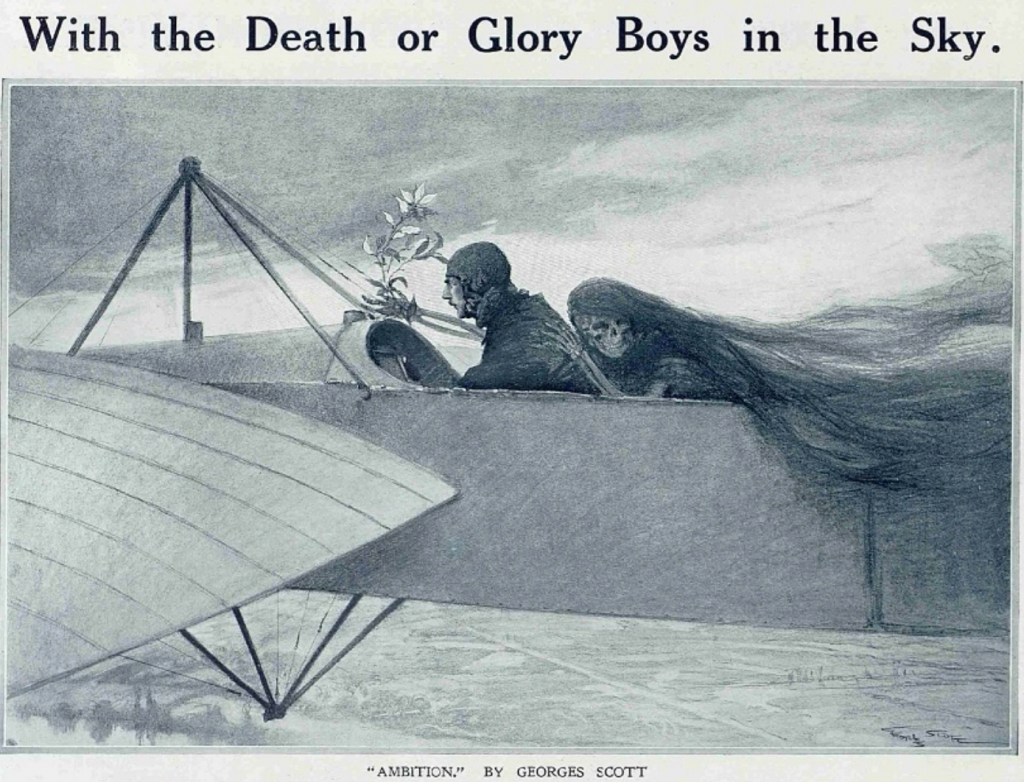

Returning to May 1911, the aviators based at Shoreham were keeping busy flying all across the south coast, testing their machines, honing their aviation skills, and entertaining the local populace. Of these aviators, judging by the news reports of the time, D.G. Gilmour and O.C. Morison were among the busiest of these young men. Going through the old newspaper archives, it seems barely a day goes by without one aviator or another taking up column inches in the publications around the country. Britain had aviation fever, and any news of these intrepid airmen was eagerly digested.

Of these two aviators, Gilmour was blazing a trail which would result in a bill being rushed through parliament by none other than a certain Winston Churchill, to “provide for the protection of the public against dangers arising from the navigation of aircraft”. On the 1st April, 1911, a number of aviators had taken the opportunity to fly over the University Boat Race between Oxford and Cambridge, reported in the Reading Mercury, 8th April, 1911:-

‘Huge crowds and several aviators witnessed the annual race between Oxford and Cambridge from Putney to Mortlake on Saturday.’ Further on it writes:-

‘The race was accompanied for the first time in its history by an aeroplane, which circled over the rival crews at a height of about 300ft. There were several other aeroplanes over the course. The aviators who had a view of the boat race from their aeroplanes were, Mr. Graham-White, who carried a passenger on his biplane; M. Hubert (biplane), and Messrs. G. Hamel, C.H. Gresswell, and Prier (monoplanes). These all started from Hendon. Mr. D.G. Gilmour, flew from Brooklands over the course.’

The Framlingham Weekly News, Saturday 8th April, 1911, reported:-

‘The presence of the aeroplanes pleased everybody, and one aviator, accompanied by a passenger who took several photographs while in full flight, responded to the hearty cheers of the huge crowd at Putney by waving his hands’

Further on it describes Douglas Graham-Gilmour’s exploits:-

‘The Bristol biplane, driven by Mr. Gilmour, followed the boat race from start to finish. In great circling sweeps Mr. Gilmour crossed and recrossed the river, and in this way kept fairly level with the crews, although he was travelling at about thirty five miles an hour. “I wanted to see the race” said Mr. Gilmour in an interview, “so I went straight down to Brooklands, jumped into my machine, and came right away. I was in such a hurry that I had no time to fill up my petrol tank. I had four gallons, and that lasts about an hour. I should not have come down at all but for that. Yes it is a novel way of seeing the boat race, and I was the only aviator to follow the crews all the way up to Mortlake. It is far the best way to see the struggle, and I was able to follow all the changes of position easily. The distance between the two boats can be gauged as easily as between two points on a map. It is a curious site to see the swing of the crews and the sweep of the oars from above, and it was the dark blue of the Oxford oars that distinguished the two boats.”

On May 15th, Police Inspector Marsh of Shoreham was given the task of arresting Gilmour at Shoreham Aerodrome, to face charges relating to the death of a young boy in a motor accident. Having been bailed, he flew from Shoreham to Salisbury to face trial on the 26th May, circling Salisbury Cathedral on his arrival. After evidence, he was acquitted by the jury after just ten minutes of deliberation. This was also the day that Churchill tried to have his ‘Aerial Navigation Bill’ rushed through Parliament.

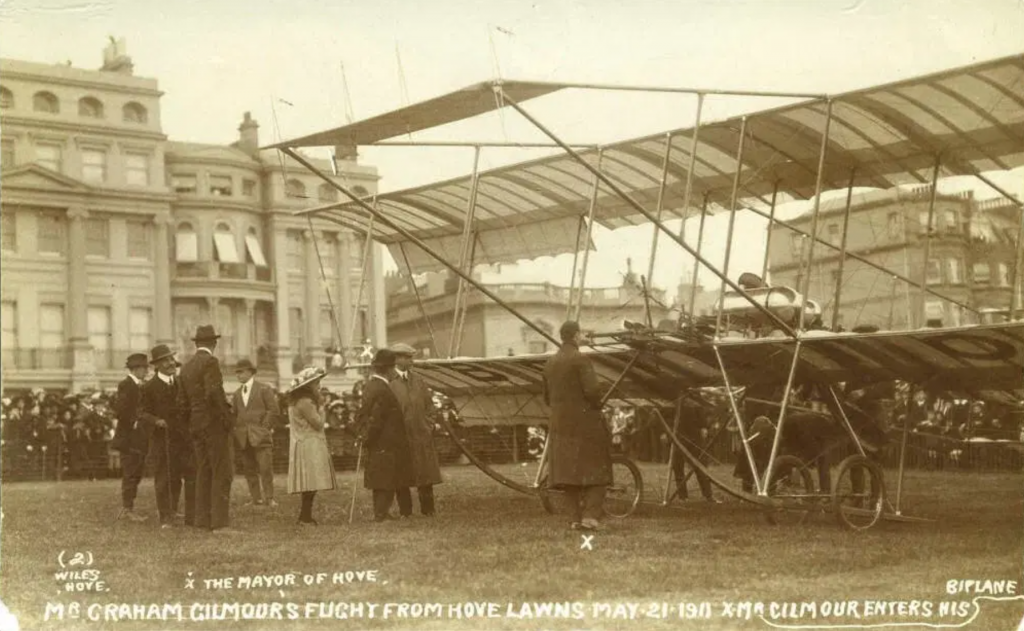

Between the arrest and the trial, Gilmour flew from Shoreham to Hove, reported in ‘Flight magazine’, 27th May 1911, it states:-

‘Mr Gilmour at Brighton. (Hove actually)

‘While flying with Mr Gordon England from Shoreham to Brighton on Sunday last, Mr. Graham Gilmour steered his biplane out to sea. When still at a good height the engine suddenly stopped and the machine commenced to glide down. Fortunately before it touched the water Mr. Gilmour got the engine going again, and rising for a short distance was able to land safely on the Lawn Gardens. Later in the day the two aviators successfully made the return journey to Shoreham.’

In the same edition of Flight magazine, 27th May, it relates more flying activity at Shoreham:-

‘Doings at Shoreham

Apart from the visit to Hove by Mr. Gilmour and Mr. England, a good deal of flying was seen at the Shoreham Aerodrome on Sunday last. Shortly after Mr. Gilmour left for Brighton, Mr. Morison was out on his Bristol biplane and made a circular trip over Shoreham and Lancing College. He then visited Brighton in his motor car, but soon after the return of Mr. Gilmour he was back at the aerodrome giving passenger flights. Mr. Gilmour and Mr. England also took up some passengers, heights attained being well over 1000 ft.’

The Great Aviation Race, June 1911.

Otherwise known as the ‘Four Kingdoms Race’, and the ‘European Circuit’, this was the biggest air race to date, with total prize money of £20,000, starting in Paris, and finishing at Hendon. Only two English aviators were entered, O.C.Morison, and Mr. James Valentine, both flying French built aeroplanes, although Morison appears not to have actually started. The Courier reported on Thursday 15th June 1911:-

‘Sixty aviators will start from Vincennes, near Paris, on Sunday morning next to compete in the great aerial race across France, Belgium, Holland and England, known as the European Circuit. The course is via Rheims, Liege, Verloo, Utrecht, Breda, Brussels, Roubais, and Calais to London. The competitors are due to arrive at Calais on June 26th. On June 27 they leave Calais early in the morning and fly across the channel to Dover, thence to the Shoreham Aviation ground at Brighton, and finally to the London Aerodrome at Hendon. There they will be met by a distinguished committee, and entertained on the following day in London. On the 29th they start for the final stage of the journey from Hendon to Paris; proceeding via Brighton and Dover.’

18th June 1911 Start of the European Circuit. Stage one, Paris to Liege.

R.Dallas Brett sets the scene in his, History of British Aviation 1908-1914, page 78:-

‘It was an imposing array of forty-three aeroplanes that lined up in three rows at Vincennes, ready for the start at 6 a.m. Since midnight a vast crowd, estimated at more than half a million people, had waited in driving rain to see the departure. A guard of 6000 soldiers and police had all their work cut out to keep control.’

Further on he continues:-

‘The perilous nature of the contest was shown up in terrible fashion on the first day. Before the control at Rheims was reached, three pilots had been killed and another badly injured.’

Flight magazine of 24th June 1911, writes:-

‘Altogether 43 of the 52 competitors who figured on the official programme were started, and 21 got through without trouble to Rheims, the “halfway” control for the day. Unfortunately, a fatality occurred during the starting operations to Lemartin on one of the Bleriots. He had made a good start, and was heading off to Joinville at a height of about 80 metres, when the machine seemed to suddenly collapse and fall to the ground, the aviator being so terribly injured that he died very shortly after admission to the hospital. Almost at the same time that this accident occurred came the news that Lieut. Princeteau, one of the officers who had received permission to follow the course, had met with a fatal accident while starting from Issy for Rheims. He had only risen to a height of about 30 metres, when apparently the carburettor of his machine caught fire, and in the sudden landing rendered necessary the monoplane capsized. The wrecked machine at once burst into flames and before anything could be done the unfortunate officer was burned to death. The third fatality occurred at Chateau Thierry, where Landron met his death in somewhat similar fashion to Lieut. Princeteau. The machine fell from a great height and the wreckage immediately burst into flames, making it impossible to rescue the pilot.’

Arriving at Calais on Thursday 29th June, the competitors were told that the stage across the channel to Dover had been postponed until first thing Monday morning, which allowed the stragglers to catch up. Flight magazine continues its coverage:-

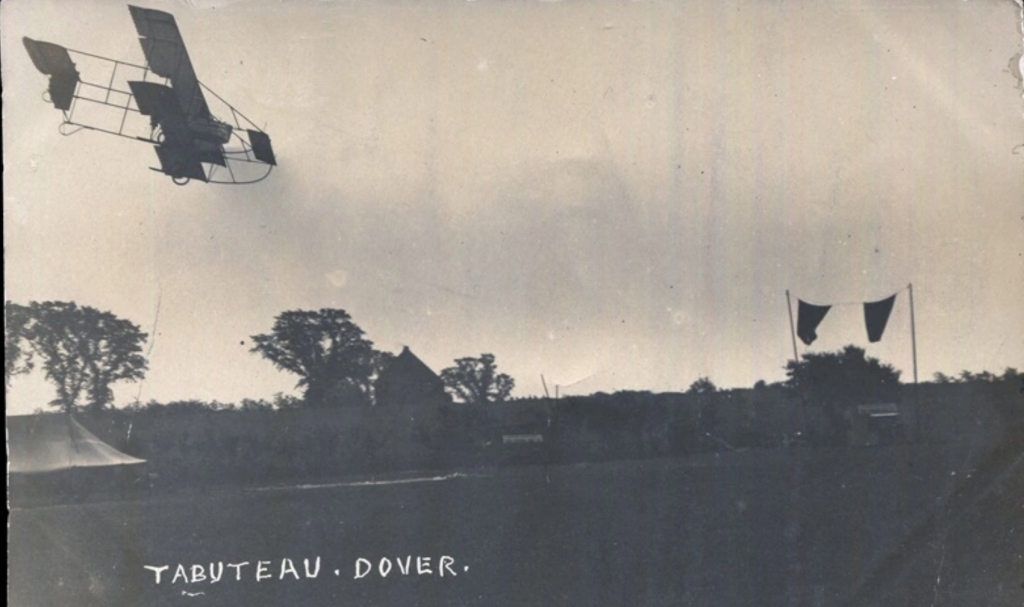

‘At four o’clock exactly, as soon as the starting rockets were fired, Vedrines was in the air, and shaping his course by the great arrow laid down at Les Baraques, he soon disappeared out to sea. At three minute intervals he was followed by Vidart, “Beaumont”, Kimmerling, Gibert, Garros, Renaux, Train, Tabuteau, Barra, and Valentine. After the last of the aviators had gone, the crowd still remained at the arodrome awaiting news of the cross channel flyers, and at six o’clock a message was received by wireless telegraphy that ten of the aviators had arrived.’

The Courier, Tuesday 4th July 1911 reported the arrivals at Dover:-

‘Aviators Make Safe Passages

Leaving Calais at four o’clock yesterday morning, and subsequently at four minute intervals, the competitors engaged in the ‘Standard Journal Europe Aviation Circuit’ made safe and speedy passages across the channel to Dover, from whence, with a stop at Shoreham Aerodrome, the journey to Hendon Aviation Ground, in the north of London, was to be made.’

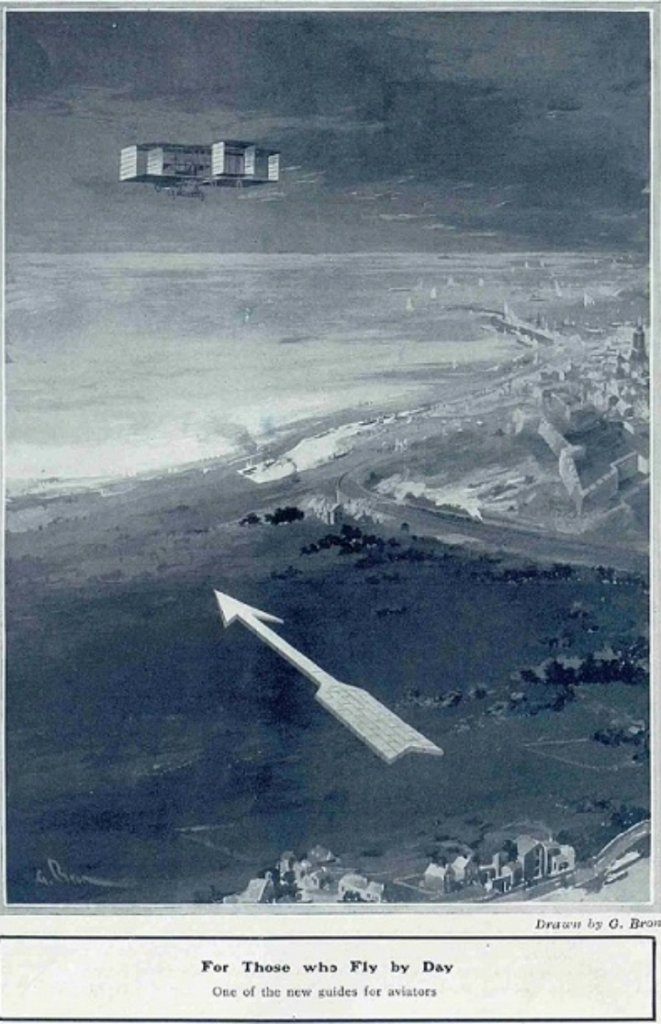

It seems amusing now, but was doubtless deadly serious at the time, but to be sure the aviators would find their way on the course, as stated in The Sphere, 24th June 1911:-

‘The organisers of the forthcoming European aviation circuit have sought the assistance of the Automobile Association and Motor Union in connection with the work of marking the course to be taken by the competitors in the English portion of the circuit. The route is chosen from Dover to Shoreham and from Shoreham to Hendon. The route will be marked by a series of large white arrows, 72 ft. in length by 12 ft. in width, placed at intervals on the ground in conspicuous places; smaller arrows, 36 ft. in length, will be used intermediately. Captive balloons are also being utilised at certain points along the route.’

(Authors note:- The imp in me wonders if they had to hurriedly turn those arrows round ready for the trip back after the last competitor had passed on his way to Shoreham?)

Preparations at the Brighton-Shoreham Aerodrome

In the same edition of Flight magazine, (Saturday 1st July 1911), which announced the official opening of the Brighton-Shoreham Aerodrome at Lancing, it reports on the work carrying on to ready the aerodrome for the first arrivals of the European Circuit race:-

‘Owing to the very bad weather this week, nothing has been done in the way of flying, though the inventor of the Valkyrie, (Horatio Barber), has been down here all week with a machine waiting for the first reasonable opportunity to get into the air. Although nothing has been done in the way of flying, great progress has been made on the ground itself in preparation for the large crowd which is expected to witness the arrival of the aviators in the great European Circuit on Friday this week. During the last few days the grand stand and ten new hangars have been completed. Refreshment booths are in the course of erection, and the band stand is nearly complete. Visitors to the aerodrome during the week, therefore, will be well catered for; they will be able to see exhibition flights every day by the Valkyrie, and the arrival and departure of those flying in the European Circuit, both on their way from Europe and on the return journey to France, which is down for tomorrow (Sunday).’

First in at Shoreham on the European Circuit: 7th and 8th Stages

Only two weeks after the official opening of the Brighton-Shoreham Aerodrome, it has the prestigious honour of being one of the control point stops in the world’s greatest air race to date, not once, but twice, as the race continues up to Hendon, then returns on the way back, back across the channel, before the finish line at Paris.

The Courier, Tuesday 4th July 1911, relays the latest race details:-

‘There was great interest and excitement at Dover, where people were astir at an early hour, and each arrival was the signal for outbursts of cheering. Leaving again at 6 a.m, Vedrines was first in at Shoreham at 07.16, and all the other competitors, with the exception of Train, who, losing his bearings, injured his machine in a descent at the village of Heighton, (Newhaven) had reached Shoreham by 07.55.’

The Aberdeen Press and Journal, Tues 4th July, 1911, picks up the story:-

‘Vedrines led off in the stage to Hendon at 07.33, and, was the first to receive the congratulations of the officials and the general public at Hendon, in which there was a large sprinkling of the French element. He effected a graceful landing at 08.34. Vidart, who left Shoreham at 07.43, was the next in at 09 o’clock. Kimmerling, who departed at 07.50, followed at 09.04. Altogether, seven completed the journey yesterday morning.’

Regarding the aviators that had been held up on this short stage, the Aberdeen Press and Journal remarks:-

‘Mishaps to Airmen

Tabuteau lost his way, and came in from the north, and in addition to Train, Barra, Gibert, and Renaux carrying a passenger, met with minor mishaps. Barra had to descend at Heathfield, near Eastbourne, and eventually arrived at Shoreham at 5.45 p.m. He left again at 6.25, and ultimately reached Hendon at 7.40 p.m. Gibert, who won the trophy for the fastest cross channel flight, 37 minutes odd, was found in a hayfield near Dorking. The machine was removed to Holmwood Common, which he left at 5.35 p.m. and gained the goal at Hendon at 6 p.m. Renaux, who had to come down at Bodiham Park, just over the Kentish border, obtained mechanical assistance from Shoreham, and took two hours and a quarter in the flight from there to Hendon, which he reached at 8.33 p.m. still carrying his passenger, M. Senouques. Train, the only competitor failing to finish, sent a message from Newhaven saying it would take him a day at least to repair his machine, damaged by collision with a wire fence at Heighton. Renaux was cordially greeted by the few remaining spectators at Hendon, among whom was his wife in a state of considerable anxiety.’

Meanwhile, over the Thames:-

On the 5th July, Douglas Graham-Gilmour flew his Bleriot monoplane up and down the Thames, causing a sensation which filled column inches throughout Britain and beyond, the first time an aviator had dared to try such a thing. Two days later, he flew down the Thames over the Henley Regatta course, The London Daily News, Saturday 8th July, reported the incident:-

‘-there were a few moments of great excitement when a Bristol biplane appeared over the course between the two races. It was manoeuvred beautifully, descending so that the starting wheels touched the water and sent up a shower of spray. It rose again, and the cheering at least equalled that given to the closest race of the day. Mr. Graham-Gilmour is believed to be the aviator.’

Gilmour’s daring display was considered a step too far, and brought him in to inevitable conflict with the Royal Aero Club, who hauled him before their committee and issued him with a flying ban for one month. This proved a most unfortunate situation for the popular aviator, as it precluded him from taking part in the coming ‘Circuit of Great Britain’ air race, organised by Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail, which carried a prize of £10,000.

There was understandable concern regarding the possible dangers of aviation, especially where crowds were gathered. As recently as 21st May, 1911, the French War Minister, Monsieur Bertreaux was killed by an aeroplane whose pilot had lost control of his machine. ‘The Daily News, Monday 22nd May, 1911, reports the scene:-

‘The tragic event occurred at the aviation ground Issy-les-Molineux, where huge crowds had gathered from the early hours to witness the start of the Paris-Madrid flying race. M.Train, one of the aviators, was seen to be in difficulties from the moment he rose from the ground. He had turned back in the direction of the sheds, and was endeavouring to avoid a squadron of cuirassiers who had been clearing the course, when he lost control and dashed in to the Ministerial group of sightseers with appalling results. M. Bertreaux, the Minister of War, was killed instantly, his arm being completely severed. M. Monis sustained a double fracture of the leg, and is believed to have received internal injuries.’

The European Circuit race finale

The competitors were now closing in on the final stages of the Four Kingdoms/European Circuit air race, flying from Hendon to the control point at Shoreham, before heading east to Dover, and crossing the channel and on to Paris for the finish line. The Evening Telegraph and Post, Wednesday 5th July, writes:-

‘From a very early hour this morning a stream of motors and other vehicles conveyed spectators to Hendon Aviation Ground to witness the start of the ten competitors in their return flight via Shoreham and Dover to Paris.’

Later in this correspondence:-

‘As six o’clock approached the aeroplanes were brought out, and practically as the hour struck Beaumont got away in fine style. Garros, Vidart, and Vedrines followed in quick succession. Then came Gibert, whose red coloured machine had a striking appearance. Renaux, the only competitor to carry a passenger was next, and apparently found his burden no obstacle to his progress. Tabuteau, Valentine, and Barra got off in the order named, and thus nine men had started within half an hour. There was some little delay owing to Kimmerling’s machine requiring attention, but the last of the ten starters got away by a quarter to seven.’

Flight magazine of 15th July 1911 reports on the aviators at Shoreham as they await the European Circuit contestants:-

‘Mr Barber made several trial flights early in the morning of Tuesday last week with a Valkyrie (Type B), taking with him one of his mechanics as a passenger, and also Miss Meeze. Next day Mr Barber started about 5 a.m on a Valkyrie with Miss Meeze, to fly to Hendon, as mentioned last week. Messrs. Gordon-England, Pizey and Fleming, who had flown over on Monday on Bristol biplanes, gave exhibition flights, and some pretty glides were witnessed by the visitors, who were already assembled to see the arrival of the aviators in the European Circuit.’

The Times newspaper, 6th July 1911, takes up the story of arrivals at the Shoreham Aerodrome:-

‘Ten airmen left Hendon early yesterday morning for Dover on the final stage of the circuit of Europe air race, organised by the Standard, and the Journal (newspapers) of Paris, and the Petit Bleu, of Brussels, and nine of them succeeded in reaching Dover after landing at Shoreham. They will leave on the cross Channel flight for Calais and thence for Paris at 4 o’clock this morning. A feature of the days flying was the fine performance of Vedrines, who occupied just under two hours on the journey from Hendon to the Whitfield Aerodrome at Dover. He wins the Shoreham £200 prize for the fastest flight between Hendon and Shoreham.’

Further on it continues:-

‘Vedrines was the first of the competitors to arrive at the Shoreham Aerodrome, where a considerable number of spectators had assembled before 7 o’clock. He was sighted at ten minutes to 7, travelling at a great speed, and in a little over five minutes had made a skilful descent amid hearty cheering. Without leaving his seat he signed the official record and was on his way to Dover. The next arrivals were Garros and “Beaumont”, the former alighting only 40 seconds before the latter, and before Vedrines had quite cleared the aerodrome. These were joined in about five minutes by Vidart. “Beaumont” was next away at 07.10, and was followed by Vidart and Garros at 07.20. Gibert in his red monoplane, descended at 07.11 and within six minutes of his arrival had taken the air again. It was nearly 07.40 before the next airman, Tabuteau, had alighted, and he was quickly followed by Renaux with his passenger, while two minutes later Kimmerling was on the scene. Of the three machines then on the ground that of Kimmerling’s was first away at 07.52, and Tabuteau’s was only a minute behind. In the meantime Barra had arrived, and after resting for half an hour started for Dover at 08.16 before Renaux, who left two minutes later. All the ten competitors had now arrived at Shoreham with the exception of Valentine, who, on finding that his engine was misfiring, descended without accident at Brooklands.’

(Meanwhile, also at Shoreham on the 4th July, 1911, the world’s first air freight delivery is dispatched)

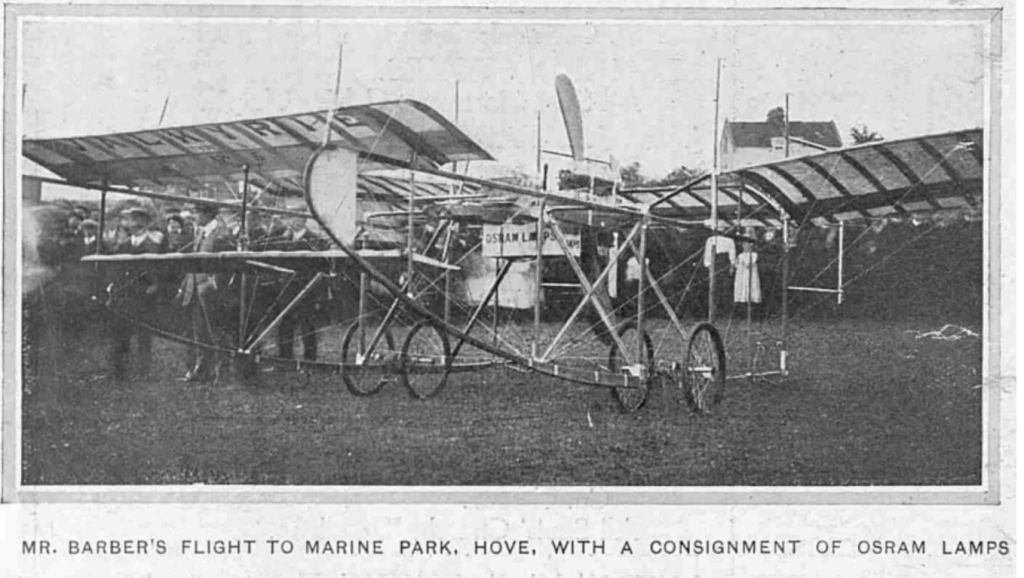

Aviator Horatio Barber made the news for the inaugural transport by air of goods- ‘The Sphere’ 22nd July, 1911, writes:-

‘Brighton and Hove’s people have had the distinction of witnessing what is believed to be the first time in the world’s history that aerial transport has been accomplished, the flight having been made on July 4 from Shoreham to Hove. Notwithstanding that a large number of people were disappointed at the flight not taking place on the 3rd, which was due to the absence of a searchlight arranged to be in Marine Park, Hove, to show the aviator where he should land, hundreds of people assembled in the park in the evening to watch the flight and descent. They were not disappointed either. The aeronaut was Mr. Barber of Hendon, and the novel and interesting exhibition was arranged in conjunction with the General Electric Company, LTD, of 67 Queen Victoria Street, London, E.C., Mr. Barber carrying on his powerful Valkyrie, type B, No.5, monoplane a consignment of Osram lamps for delivery to Messrs. Page and Miles, LTD, Western Road, Hove. Arrangements were to have been made to enable the monoplane to be illuminated with Osram lamps, but this was not carried out.’

European Circuit final stage, 7th July.

This race had highlighted how far ahead France were from Britain in aviation design, construction, and piloting, with James Valentine, the only Briton who actually started, and despite his valiant efforts to continue in the race, eventually gave up after encountering problems on the Hendon to Shoreham leg. So Britain’s only involvement at the final stage was Maurice Tabuteau, who was flying a Bristol biplane, built by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, Ltd, at Filton, Gloucestershire. Flight magazine of 15th July, 1911, describes the Paris finish:-

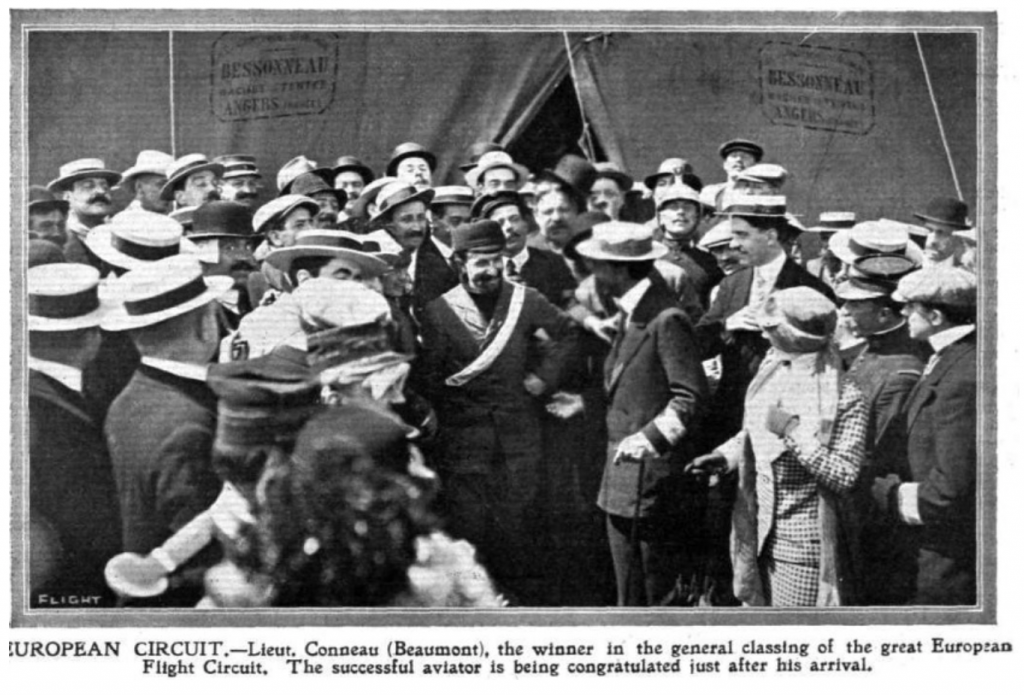

‘At Vincennes there was another huge crowd, among whom was General Roques and several other highly placed Government officials. At half past eight an extra sharp eye detected a speck in the sky, while an expert ear caught the sound of the unmistakable hum of a Gnome motor. Within a few seconds the news had spread round the concourse, and the cry went up, “They are here!”. The next question was “who could it be” as the news of Vedrine’s accident had come through, and it was realised he could not be the arrival. It only needed a few minutes, however, to bring the monoplane nearer in to view, for it to be seen that it was the Deperdussin monoplane, and of course piloted by Vidart. He landed at 8.37, and was at once carried shoulder high to the Deperdussin shed to the strain of the Marseillaise. There was then a delay of seven minutes before the arrival of Gibert, who it should be remembered is the only monoplanist who had completed the full distance on the one machine, whereas the others have changed their machines several times. The third to arrive was Garros, at 9.15, and then the others came in at fairly lengthy intervals, “Beaumont” being fourth at 9.26.’

‘The overall winner was Andre Beaumont, with a total race time of 58 hours, 38 minutes, followed by Roland Garros*, on 62hrs, 17 mins, 3rd place was Vidart, on 73hrs, 32 mins, and Vedrines, who had led for much of the race, came in fourth with a time of 86hrs, 34 minutes, having damaged his machine while landing on the next to last leg.

* (This was the Roland Garros whose name would be given to a rather famous tennis arena in Paris).

Oscar Morison flies from Paris to Shoreham.

While the worlds press followed the race around Europe, aviators elsewhere continued to push the boundaries of what could be achieved in their fragile looking aeroplanes, and O.C.Morison was one of these intrepid aviators. He had hoped to race his new Morane monoplane in the European Circuit, but it wasn’t ready in time, and actually picked it up from the factory in Paris just after the race had finished. ‘The Daily News’, Monday 10th July, 1911 reports:-

‘Paris to Shoreham in 5 Hours

A remarkable feat was accomplished by an English aviator on Saturday (8th July), Mr. O.C. Morison (one of the most successful flying men in this country) getting from Paris to Shoreham with only two brief stops, and setting up what must almost be a record. Mr. Morison showed considerable pluck, for he did not announce the attempt, and there was consequently no tugs or torpedo boats out to render assistance should he require it. In five hours the aeroplane covered 250 miles, giving the high rate of 50 miles an hour, and this included the stops. Mr. Morison started his monoplane at Paris shortly before noon, and averaged a mile a minute to Calais. Stopping just long enough to replenish his petrol tank, he went on straight for Dover, and mounted at a great speed to a height of nearly two thousand feet, seeming through the heat haze to be almost among the lower clouds. The channel was crossed in half an hour, and, passing over Dover Castle, Mr. Morison made straight for Eastbourne, and descended in a field there at ten minutes to four. A quarter of an hour was occupied in once more taking in petrol, the engine was again restarted, and just before five p.m, the machine descended at Shoreham.’

Coming up in part four:- Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Daily Mail, offers £10,000 as a prize for the aviator that wins a Circuit of Britain race. Shoreham gets busy, more top aviators set up at the newly expanded facilities.

Andy Ramus 2021

For the additional article chapters follow the links: